Trust in Science is Changing

What that means for public health

Image credit: Thalia Patrinos

by Hanna Webster

January 18, 2022

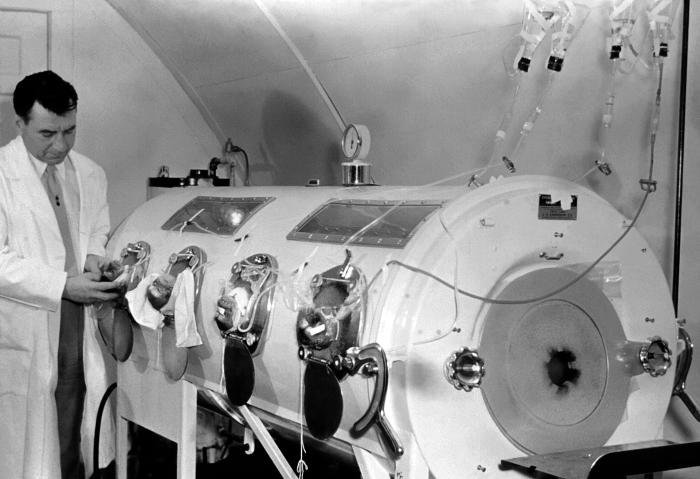

On October 13, 1959, an ambulance raced Mario Monroy’s grandmother, Frances May Stuppy, to the hospital in Saint Joseph, Missouri, where she died two days later. She had polio, a contagious and deadly virus that received vaccine approval in 1955. Frances’s husband, John, also contracted the disease. In an adjacent hospital room, John heard the sounds of Frances’s iron lung, a device that acts as an artificial respirator to help paralyzed patients breathe. When he heard the iron lung hiss to a stop, he knew she was gone.

Click on the graph to enlarge it. Image credit: The COVID States Project, Report 63

At Frances’s funeral, a transparent plastic sheath over the coffin separated her from the outside world to deter any lingering viral particles from infecting those attending. Frances’s death deeply affected her daughter, Marie, a young girl when her mother died. Marie, Mario Monroy’s mother, speculates that her mother was not vaccinated against polio and worries that families not vaccinated against COVID-19 are suffering a similar fate.

Yet even his grandmother’s harrowing death from a dangerous virus did not convince Mario to get inoculated against COVID-19.

During the first few waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, the US had only masks, social distancing, frequent handwashing, and government lockdowns to curb the spread of the virus. Now, vaccines and booster shots are available for many. If everyone in the world were vaccinated, we could make debilitating COVID-19 sickness a thing of the past. Why are some in the US, like Mario, not taking that opportunity?

The COVID States Project offers some insight. In 2021, several universities conducted surveys to understand the US public’s response to the COVID-19 vaccine. The researchers released a series of preprint reports—published before the peer-review process. Report 63, The Decision Not to Get Vaccinated, from the Perspective of the Unvaccinated, reported that 15% of unvaccinated respondents (180 people out of 1,205) cited lack of trust in institutions, including lack of trust in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as a reason why they had not gotten vaccinated.

Science regularly refreshes what it deems the truth. A tenet of the scientific method involves updating our understanding once we gather new information, like masks preventing coronavirus transmission. But heavy criticism of changing findings and mistrust in scientific conclusions and institutions remains steadfast in millions of Americans and can be a sign of anti-science attitudes.

“People prefer certainty—we want to think scientists and doctors know everything at all times,” said Katherine Ognyanova, associate professor of communication at Rutgers University and a researcher in the COVID States Project. “Experiencing the way scientific knowledge changes over time can be very unsettling.”

How did we get to a place where so many fear hidden ingredients in clinically safe vaccines, like microchips, toxic chemicals, and even the coronavirus itself? And is reconciliation possible?

Our choices are not insular, one-dimensional units. They are tethered to our sense of self, moral compass, and social network. Each of these concepts play a part in how deeply misinformation has burrowed into US culture.

Exposure to widespread misinformation may be to blame for vaccine misperceptions, said Ognyanova. Her team on the COVID States Project asked respondents to rate the truth of four popular myths about the COVID-19 vaccine: that the vaccine alters human DNA, contains microchips or the lung tissue of aborted fetuses, the vaccine causes infertility. As shown in Report 60, Vaccine Misinformation from Uncertainty to Resistance, 20% of Americans surveyed thought at least one of these statements was true, although research had debunked all four myths. This effect remained even after controlling for socioeconomic and demographic factors like income, age, and race.

Historic photo of an iron lung. Image credit: Centers for Disease Control & Prevention

For example, Mario, the family friend who lost his grandmother to polio, is skeptical of the nascent mRNA technology in the COVID-19 vaccine—he read that lipid nanoparticles in the vaccine spread throughout the body and cause damage. In reality, lipid nanoparticles, or fatty capsules, play a key role in protecting the mRNA and carrying it to the right places in the body. And Reuters debunked a myth that lipid nanoparticles contained microchips—people mistakenly thought the prefix ‘nano’ referred to computers instead of a unit of size.

Mario said he often listens to NPR while working as a delivery driver—not just NPR and CNN, but Fox News, conservative AM radio talk shows, and InfoWars, a conspiracy theory site run by controversial figure Alex Jones. When presented with information that contradicts his beliefs, he said, he sometimes finds himself saying, ‘Hmm, I never thought of it that way.’ Mario did admit to some level of bias. “There’s something inside me that does not want to be told what to do. I am scared of losing my freedom. I find myself being biased in that way.”

“Science regularly refreshes what it deems the truth.”

Unfortunately, misconceptions do not simply remain in our minds; they get recirculated through conversations with family and friends and through the internet. The COVID States Project found that the level of trust in science plummeted by more than half in the unvaccinated sample. While the unvaccinated sample was smaller in this study, these findings represent a marked difference in how the vaccinated and unvaccinated see and interact with the world.

Like the swift spread of airborne particles from a contagious virus, the internet has become a breeding ground for all manner of pandemic opinions. Ulrike Hahn, a professor of psychology at Birkbeck, University of London, studies how misinformation proliferates through online social networks. Early in her career, she grew curious about whether scientists could develop “objective yardsticks” to measure whether an argument is weak or strong. She said the strength of arguments and how we form them depends partly on how we get our information and our examination of that information’s credibility.

Let’s say you hear that a cougar has been found in your neighborhood. Then another person tells you. Then, another. This claim gains strength each time you hear it. You use this information to update future decisions about what you should do regarding a dangerous animal near your home.

But what if all three claims came from the same person? There was only one potential sighting; it just reached you in three different ways. This, Hahn posited, is presumably different from three separate sightings of a cougar. And this is the nature of social networks. It highlights how the spread of information on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram can skew the public’s belief about the importance of an issue. As one hears a claim repeatedly, it can start to gain what might seem like credibility.

Matt Motta, a political science professor at Oklahoma State University, believes anyone of any political party is susceptible to echo chambers common in social media. Motta’s research has found that access to the internet helps explain vaccine resistance. “You need to have access to misinformation to believe it,” said Motta. He also found that our views about the world form part of our social identity. “If something is central to your identity … or sense of self, well, it’s a lot easier to change your views on a policy issue or to not vaccinate than it is to fundamentally change who you are and how you think of yourself,” Motta said.

Click on the graph to enlarge it. Image credit: The COVID States Project, Report 63.

It’s not just internet echo chambers that damage trust in science; it’s also a lack of trust in institutions in general. Ognyanova said trust in social institutions has declined steadily over the last few decades, but “scientists and doctors remain among the most highly trusted categories.” The pandemic has changed things, though. “The measures taken to curb the spread of COVID-19 have been very heavily politicized, so political mistrust now has a considerable effect on health-related attitudes,” said Ognyanova. This is clear in the data from the COVID-19 States Project.

“We … find that confidence in institutions remains a very strong predictor of getting vaccinated—or refusing a vaccine,” Ognyanova said. “People who don’t trust the government and mainstream media are both more likely to be exposed to vaccine misinformation, and to be vaccine-resistant.”

What’s to be done about mistrust in science? Scientists are studying trust to help answer that question. Researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign found that those who reported more trust in science, or what the researchers deem “misplaced trust,” were more likely to spread misinformation if it contained scientific references. “Misplaced” is the key word here. Psychologist Thomas C. O’Brien, one of the study's authors, said he and his colleagues are not discouraging people from trusting science—but trusting science should not become a substitute for critically analyzing a piece of information. “This is difficult detective work,” O’Brien said.

O’Brien and his colleagues crafted two passages. Both contained activist testimony, but only one contained scientific references. Both passages were rife with buzzwords and phrases like “those who attempt to obscure the truth,” “support from terrorist groups,” and “attempted governmental cover-up.” Someone who identifies strongly with science might see a journal article from Princeton University and use it as a cue of validity, and without further thought, miss the buzzwords later in the passage.

One trait did have a protective effect against intent to spread misinformation—more knowledge of the scientific method. Those who scored higher on a science literacy test were less likely to believe or disseminate the passages’ findings. This study shows that knowing the process behind science is crucial to understanding whether information is accurate.

That doesn’t mean we have to become scientists to access facts. “Much of what we come to believe comes from the testimony of others,” said Hahn. Many phenomena are invisible to the eye, so we build our worldview around trusting experts who have seen them. For example, if an astronomer tells you a meteor is approaching earth, and you find this person trustworthy, that testimony can become the basis for your belief. So how far should we go in responding to the testimony of others? How much should we use others’ accounts to inform our beliefs about the world?

We want to have faith that scientists gather credible, statistically significant, and ethical evidence, which is usually the case. Still, we need a healthy dose of skepticism when evaluating this evidence.

Just as Mario experienced when searching for more information on the COVID-19 vaccine, many pieces of information use the veneer of science to communicate mistruths. This makes it increasingly difficult for individuals to discern the validity of sources, and it’s part of the reason why vaccine misinformation has proliferated at the level it has.

Accurate science communication plays a critical role in fostering trust in science. Motta said this should be a two-way street—academics should try to communicate with the public in more approachable ways, and journalists should develop trustworthy relationships with academics. Motta said he discourages sensationalist language that might sway readers and encourages open dialogue so each tier can communicate effectively.

It is not enough to communicate—it also matters how we do so. When conversations get heated, trust and misinformation experts urge us to look past our differences and come from a place of compassion. Telling someone they are wrong or acting hostile backfires when communicating about contentious topics. “It is very tempting to want to correct people; we have to remember that correcting people isn’t always the most effective solution,” Motta said.

Motta and Ognyanova explained that what works is meeting people where they are. “The way forward isn’t to cut off people’s internet access; it’s not to fundamentally change their identities,” said Motta. “It’s to do the surveillance work necessary to know why people believe what they believe, and to then make an effort in our [communication methods] to talk to people on those terms.”

Hahn said that combating misinformation and a lack of trust in science will require a radical change in the structure of social media itself. In her eyes, we cannot just teach media literacy and hope the problem goes away, because the pathways that allow misinformation to proliferate will still exist.

“The world becomes different when you start to give [misinformation] a megaphone and a podium,” Hahn said. “With the pandemic, we have been able to observe that in real time. You can watch myths being born and spreading and having real-world consequences.” Hahn is now organizing a workshop with her colleagues on science communication as collective intelligence.

“There’s no silver bullet,” Motta said. Complex problems do not have simple solutions.

As for families like the Monroys, it is unclear whether they will see eye-to-eye. Mario discovered yoga and meditation and said he wants to remove himself from the media-sphere. He said he feels guilty that so much deep-diving in the media took the place of human interaction and momentum toward his goals. “I’m trying to focus on myself,” he said. “If we want to change what’s happening, we have to change ourselves … at the end of the day, solutions lay with individuals.”

As voracious consumers of information, some parts true and some not, the best we can do is remain critical of the information we seek and take things one calm conversation at a time.

Hanna Webster

Hanna Webster received a bachelor of science in neuroscience and creative writing in 2018 from Western Washington University, and is a graduate student in the Johns Hopkins University Science Writing Program. She writes about neuroscience, biology, and public health. Her essays and articles have appeared in Jeopardy Magazine and Leafly. When Hanna is not writing, she enjoys consuming many other art forms such as photography, poetry, creative nonfiction, and live music. She lives in San Diego, California.