The Theory of Hope

Goal-related, relational hope helps children succeed

Image credit: Tara Holley

by Julia Brown

January 18, 2022

At eleven years old, I couldn’t see my life beyond what it was at the time. I was an only child responsible for a mentally and physically disabled single mother. Each morning, I awoke to the sound of my mother’s alarm and snuck into her room to turn it off before getting dressed. I packed my lunch (also hers when she had a job) and ate a bowl of cereal or frozen waffles for breakfast. Before heading to the school bus, I made sure she was out of bed and had taken her meds. After school, I came home, made dinner for us, worked on homework, and did the dishes. Before bed, the last thing I did was ensure she had taken her meds again. The weekends were for cleaning. I vacuumed, scrubbed the bathroom, did the week’s laundry, and picked up around the house. I relied heavily on my grandparents for some sense of stability, as they often allowed us to live in one of their two properties and brought us groceries regularly.

It wasn’t until I attended a summer camp for underserved youth that I learned my present didn’t define my future. Compass for Kids’ Camp Care-A-Lot sets children up for success by teaching them hope. After attending the camp, I considered what I wanted to do with my life, where I wanted to go, and what I wanted to achieve, knowing that not only was anything possible but that I would always be able to find supportive adults along the way. For once, I was hopeful that my future was uncharted.

Julia Brown (right) and her mother. Image courtesy of Julia Brown.

As described by the late psychologist C. R. Snyder in his research on hope theory, hope is a motivational mindset based on successful goal planning, effective use of goal-directed energy, and creating pathways toward achieving those goals. His review of research on the topic showed that those with higher hope consistently did better in all areas of life, including physical and mental health.

Camp Care-A-Lot, which had long understood the importance of hope, implemented a program called Kids at Hope in 2001. Inspired by Snyder’s work, the program helps children create hope and optimism to enable success—“no exceptions,” as their tagline says. John Parsi, president of Kids at Hope and executive director of the Center for the Advanced Study and Practice of Hope at Arizona State University, says the program follows a cultural approach to building hope. Adults influence a child’s ability to hope by providing structure and support.

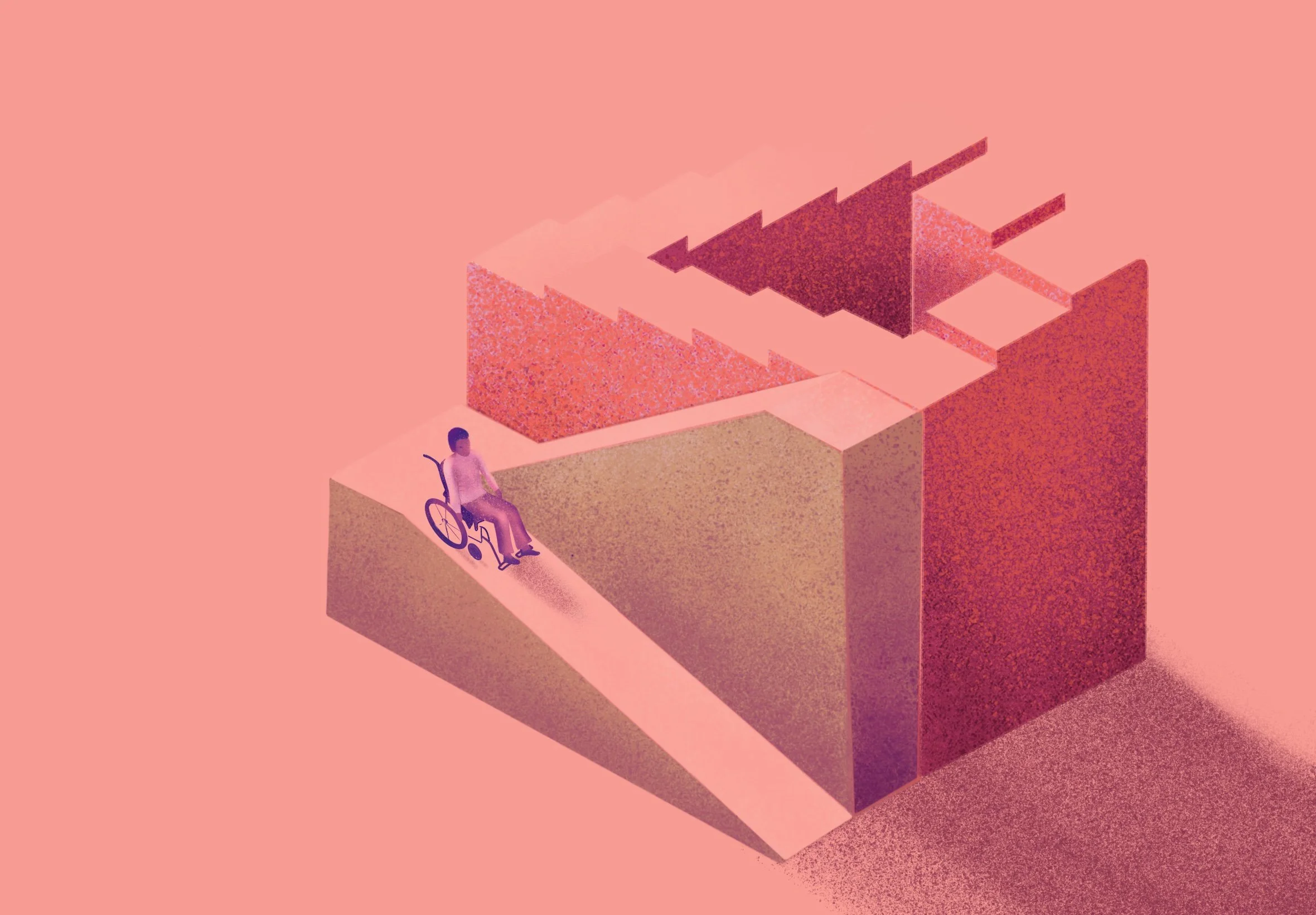

“I don’t believe in the ‘pull yourself up by your bootstraps’ individualistic narrative,” said Parsi. “There are a lot of people who could have great success but simply don’t have a structure in which they can succeed. We need to create a culture in which a child is told, ‘You can be successful, and you are successful all the time.’”

The French philosopher Gabriel Marcel, described hope as “something that occurs between persons—a relational process inspired by love.” Kaye Herth, dean emerita at Minnesota State University, Mankato, said hope helps build personal success through relationships. “Others are critical in that process through the nurturing and sustaining of that hope.”

Camp Care-A-Lot is a real-world case study of relational hope theory in action. “The fact that so many campers come back as counselors or volunteers, I think, is proof that the Kids at Hope philosophy works,” said Eydee Schultz, Camp Care-A-Lot’s first vice president, executive director, and camp director, now retired. Each year, many Camp Care-A-Lot staff are former campers, including the current director. The Kids at Hope program was created almost 30 years ago and has been implemented nationwide at institutions like Camp Care-A-Lot. Several former campers have gone on to earn their undergraduate and graduate degrees; they have made successful careers in the military and trade professions, grown loving and hopeful families, and excelled in their professional careers. I’ve met many former campers who cite their camp experience as a driving factor to their success. It was for me.

Let’s take a closer look at the science of hope. One of the key outcomes of being hopeful is success, or what Snyder called goal attainment. Psychologist David Feldman and colleagues at Santa Clara University tested how hope affected the success of 162 college students over one semester. The study determined that participants with higher goal-specific hope experienced higher success rates than students with general hope.

“Being hopeful isn’t about being blindly optimistic.”

“If someone has high hope, they are likely to perceive themselves as able to reach their goals and be successful. In turn, once someone does attain a goal, there is likely a reciprocal relation [and] they are likely to continue to have high hope, and so on,” explains Crystal Bryce, assistant clinical professor and associate director of Research for the Center for the Advanced Study and Practice of Hope at Arizona State University.

Success can and should look different based on each person’s individual goals. Parsi explains that his measure of success wouldn’t be fixing his transmission. He doesn’t know anything about fixing cars, but repairing someone’s car might constitute a successful day for his local mechanic.

“Everyone has their lived experiences, and we need to be aware of those lived experiences and not ignore or push them away. If we want to help someone be hopeful, we need to support them—sometimes guide them—in their autonomous, self-directed goals,” said Bryce. “When we allow others to set their own goals, they are likely to be more motivated to work to pursue those goals, and more hopeful.”

A 2002 study by Snyder and his team followed more than 200 college students over six years. Participants with self-reported low hope had lower GPAs (2.44) than those with high hope (2.85). Additionally, those with low hope had a graduation rate of 40.27% versus 56.52% of high-hope participants and were dismissed because of poor grades at a higher rate (25% vs. 7.10% of those with high hope).

“Being hopeful requires success, no matter how small the successes are. There’s a circle intertwining the two,” said Schultz. Success does not come only from achieving one’s major life goals. Instead, people should look for small victories along the way to maintain their hopefulness, Schultz said. It helps to break large goals into smaller achievements to make the main goal seem more attainable.

Being hopeful isn’t about being blindly optimistic. Schultz, Parsi, and Snyder recognized the difference between the two, describing optimism as passive thinking, contrasted with a sense of hopefulness that requires active participation. When faced with inevitable failure in reaching a certain goal, an optimistic person might say that things will be better tomorrow, then wait for tomorrow to come. A hopeful person, faced with the same failure, will reassess their strengths and determine a new path to success based on what they learned from failing. Even failures, Parsi explained, can be reframed as opportunities for continued success.

When I failed my freshman year of college, I was devastated. I always excelled at school and confidently applied to my dream college. Faced with either continuing to struggle where I was or returning home to attend community college, I reassessed my goals. My goal wasn’t really to attend my dream school. My goal was to get my degree. Knowing how hard my freshman year was, I determined the best path for reaching my goal—obtaining a college degree—was to return home and attend community college. Two years later, I graduated with an associate’s degree.

I wanted to give up at times. I thought there was no feasible way of succeeding. But each obstacle that I’ve encountered in my life—addiction, unhealthy relationships, failure in my first year of college, my father’s death the weekend I was scheduled to move to another state, imposter syndrome in my corporate life—I have faced as someone knowing she is capable of success. Through the hope instilled in me at a camp applying hope theory, I’ve been able to find mentors and the strength to keep going.

Julia Brown

Julia Brown is a writer whose career spans print journalism, organizational communications, web content creation, and social media management. She currently focuses on agriculture and plant sciences. Julia received her bachelor's in interpersonal and organizational communications from the University of Illinois at Springfield and is pursuing her master's degree in science writing from Johns Hopkins University.