Helping Those Who Can’t Ask for Help

Navigating post-stroke aphasia

by Costanza Frakes

January 18, 2022

"Idon’t want to ride on the sewing machine.”

Ten years ago, my mother suffered a stroke. My mom’s thoughts are still there, but getting them out is a challenge. It’s easy to see when she’s at a loss for words. She pauses, she gets flustered, she makes vague noises—but something is missing. Sometimes, her words are switched around. At first, the switches were outlandish and easy to spot. Her wheelchair became her sewing machine. Now, it’s more subtle. Left becomes right. Me becomes you. No becomes yes. She says the opposite of what she means without any hesitancy.

This byproduct of her stroke is called aphasia. “It is not a disorder of intellect, and it is not a disorder of memory,” said Maura Silverman, founder of the Triangle Aphasia Project Unlimited. “It’s an access disorder.”

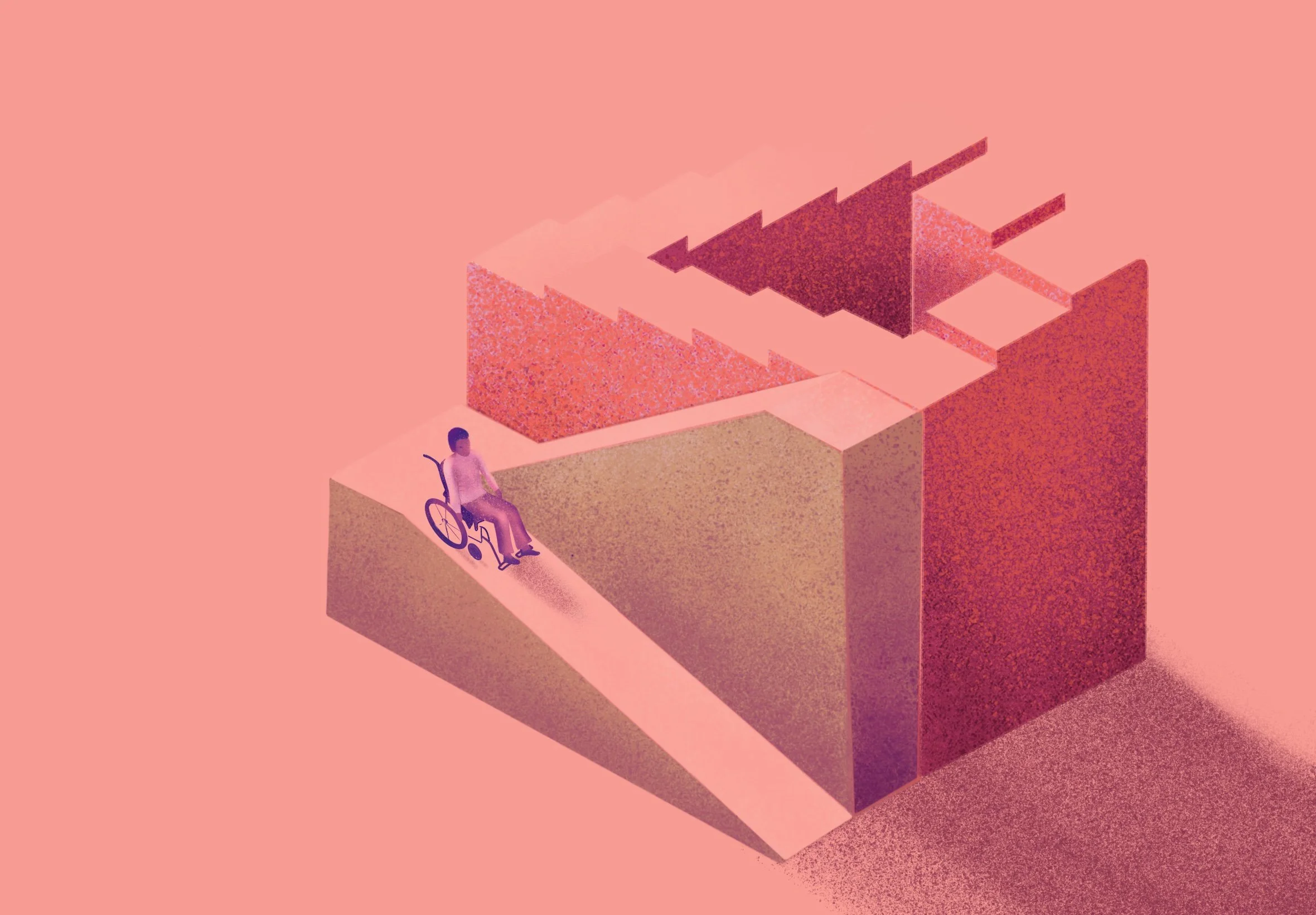

Individuals with aphasia have a harder time accessing the four modalities of language—reading, writing, listening, and speaking—and connecting them to the thoughts in their heads. Some individuals are more likely to struggle to find words, while others use the wrong words.

Aphasia can increase the risk of depression and other mood disorders, but it can also impede getting help. From assessments for depression to post-stroke procedures, existing forms of support need to change to protect a vulnerable population.

Any traumatic or life-altering event, such as a stroke, is a risk factor for depression. Based on a review of the scientific literature, a pair of researchers from the National Institute of Technology Calicut in 2018 reported that approximately one in three stroke survivors suffers from depression. The number is even higher for stroke survivors with aphasia. A 2000 study showed the number of aphasic patients with depression may be as high as 70% within the first three months after a stroke. The same research also showed that the prevalence of major depression increases as time goes on.

Diagnosing depression

Identifying depression in aphasic patients is a tricky matter. Depression is typically diagnosed through a survey, requiring responses to written or verbal questions. For a person with aphasia, these surveys are difficult to process and respond to accurately. Aphasia-specific assessments do exist, but these assessments can be costly, they are infrequently used due to lack of training, and research into their efficacy is limited.

In 2016, when Dutch researcher Mariska van Dijk and her colleagues performed a meta-analysis of available studies, they found six assessments for depression in those with aphasia. Of those, none were “sufficiently investigated,” and the existing studies had “low methodological quality.” One study from a 1998 issue of Clinical Rehabilitation reports that “[patients] were excluded from the study if they were unable to complete standardized questionnaire assessments due to a language impairment.” The language impairment referenced was aphasia, the very issue the assessment was designed to support.

“We [the aphasia treatment community] do spend a lot of time in that testing area,” said Silverman. Regardless, she cautioned against relying on assessments. The process can waste limited health insurance-subsidized therapy hours, as a single assessment can take multiple hours. Instead, she recommended avoiding the sterile and often lengthy testing phase of treatment and just talking with the individual using conversation techniques for those with aphasia. Using a plain Sharpie marker and a pad of paper is a more effective engagement method. “I can find out more than someone who is relying only on standardized tests,” she said.

The roots of the issue

Speak to anyone who works with aphasia patients closely and you’ll hear one word crop up again and again: isolation. The vast majority of people with aphasia—92%—feel a deep sense of isolation. Isolation may be the culprit for the epidemic of depression in those with aphasia and can stem from a variety of factors, including environment, family and friends, and even lack of confidence.

“Our world is so language heavy,” said Lynsey Keator, a speech-language pathologist and doctoral student at the University of South Carolina (USC) Aphasia Lab. “When language becomes a barrier, things become very, very isolating.”

Keator leads most of the USC Aphasia Lab’s community outreach programs, including their aphasia recovery groups and a monthly restaurant outing. She briefs restaurant staff on aphasia and techniques for communication and then works with people with aphasia and their caretakers to facilitate a smooth outing. The simple task of eating at a restaurant becomes a mammoth challenge when individuals struggle to communicate, so Keator works with both restaurant staff and those with aphasia to bridge the gaps and increase accessibility.

Family and friends, too, benefit from similar lessons.

“Not only do they not know what aphasia is, but there’s this inaccessibility to communicate with somebody who has aphasia and a fear of not doing it the right way,” said Keator.

At the Triangle Aphasia Project, Silverman hosts “How to Speak Aphasia” courses once a month for friends, families, coworkers, and others who want to support someone with aphasia. The courses cover the basics of communicating with loved ones with aphasia to ensure that those relationships can be maintained.

As Silverman shares during courses, a big component of isolation is also lack of confidence. Those with aphasia recall their communication abilities from before the aphasia and recognize that they are making mistakes or struggling to find the words. As time away from communities and hobbies increases, it becomes progressively harder to jump in and rebuild those connections. Starting from zero is incredibly difficult, and it’s all too common.

“We talk about reengagement,” said Silverman. “But what if they were never disengaged?”

Support networks are key

General Michael Hayden, the former director of the US Central Intelligence Agency and the National Security Agency, suffered a stroke in 2018. He, too, has aphasia; in a recent National Public Radio (NPR) interview, he shared that he was attending weekly aphasia support groups.

My mother listened to that interview, and it was the first time she had heard of aphasia support groups. She had never been directed to one by a medical practitioner. In fact, no medical practitioner had told her of her aphasia. She found out from reading her chart after being discharged from the hospital, something that still happens today.

Her subsequent searches for a local or online aphasia support group proved overwhelming. Aphasia.org has plenty of listings, but it was impossible to digest for someone struggling with reading. I was on the phone with my mother when she first looked for a group. I heard her sigh and say she would try again later.

Medical providers should immediately connect patients to a speech-language pathologist, preferably one trained in post-stroke mood disorders like depression, in addition to other professionals like physical and occupational therapists. Speech-language pathologists, in turn, should stay up to date on local or online support groups. If someone with aphasia presents signs of major depression, the speech-language pathologist should refer the patient to mental health professionals trained in adaptive communication strategies.

Outreach and awareness

One of the reasons these resources aren’t immediately made available is a lack of awareness. Though as many as four million Americans currently suffer from aphasia, most Americans have never heard of the word.

“A lot of [isolation] stems from aphasia being an invisible disability,” said Keator. “Someone can be sitting at a table at a restaurant, and you wouldn’t know that they have aphasia until they start talking.”

In his NPR interview, General Hayden mixed up left and right, just as my mother does. When Silverman met General Hayden after the interview, she specifically thanked him for his mistakes.

“I think it’s giving permission for other people to take chances and to go back out there,” said Silverman. “It’s inclusion.” It’s easy to want to brush everything up and leave mistakes on the cutting room floor, but those mistakes provide visibility for others with aphasia. More visibility, in turn, allows for more chances for connection and understanding. This is vital for reducing isolation.

It’s never too late to make a difference

“You are a changemaker,” said Silverman in her presentation to families and friends. There were wives and husbands, children and grandchildren, friends, caseworkers, and therapists. Some were there for a loved one in their first two months of aphasia. Some, like me, were there to support someone who had been struggling long-term. All of us were looking to see how we could improve the lives of our loved ones struggling to find words to express themselves.

There’s a longstanding myth that recovery plateaus after six months. Both Keator and Silverman firmly reject this. It’s important to do what we can immediately, because confidence and relationships can be negatively affected by a lack of action and support. But it’s also important to know that the road to recovery can be long. It’s important not to be discouraged. It’s important to work together, advocate for those who cannot easily advocate for themselves, and continue to make strides.

Now, 10 years after her aphasia first reared its head, my mother has come a long way. She has reached out, seeking assistance for depression. We have been looking into support groups and attended a workshop about aphasia together. There is so much that my mother wasn’t given access to immediately. But we haven’t stopped looking. We haven’t stopped trying. We will never give up.

Costanza Frakes

Costanza Frakes is a training and development coordinator with a passion for learning and education. A former secondary math and science teacher, she continues to enjoy the odd math problem, interesting rock, and the science of baking.