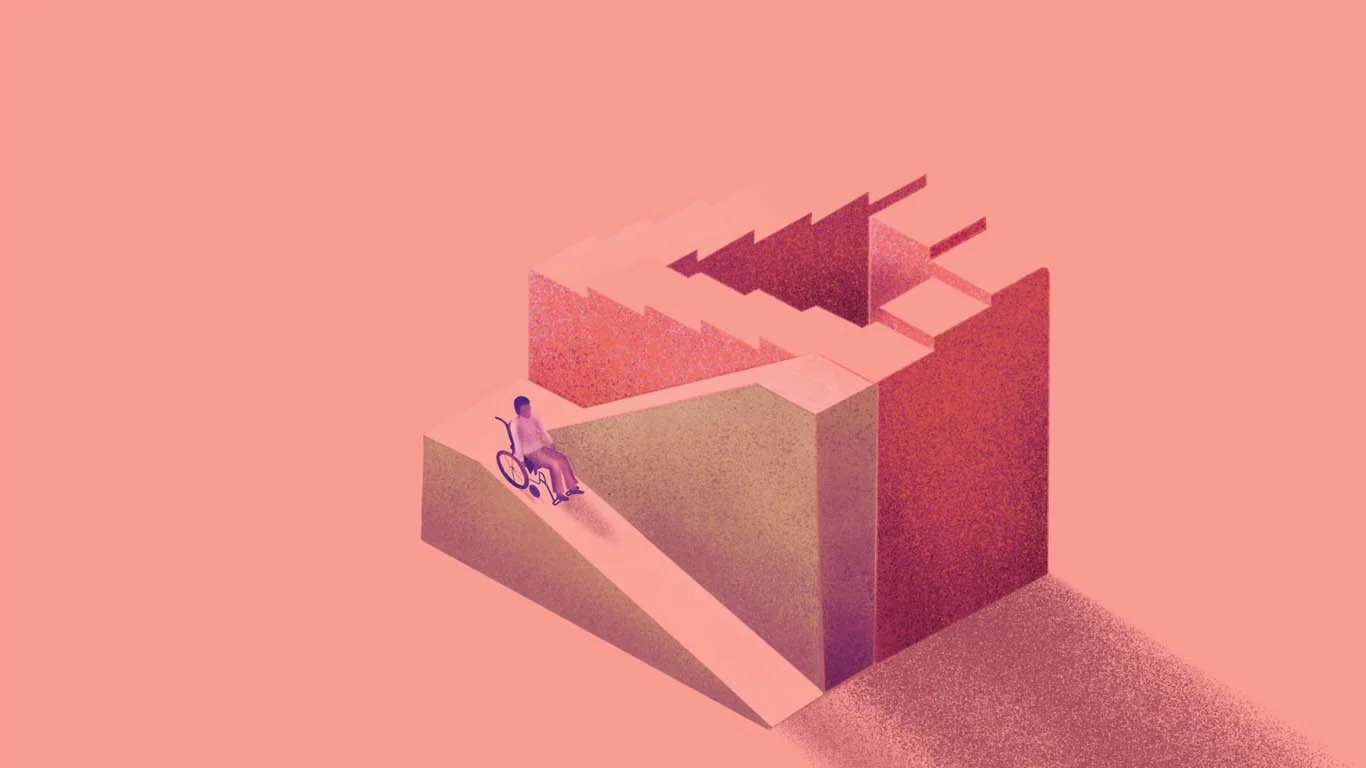

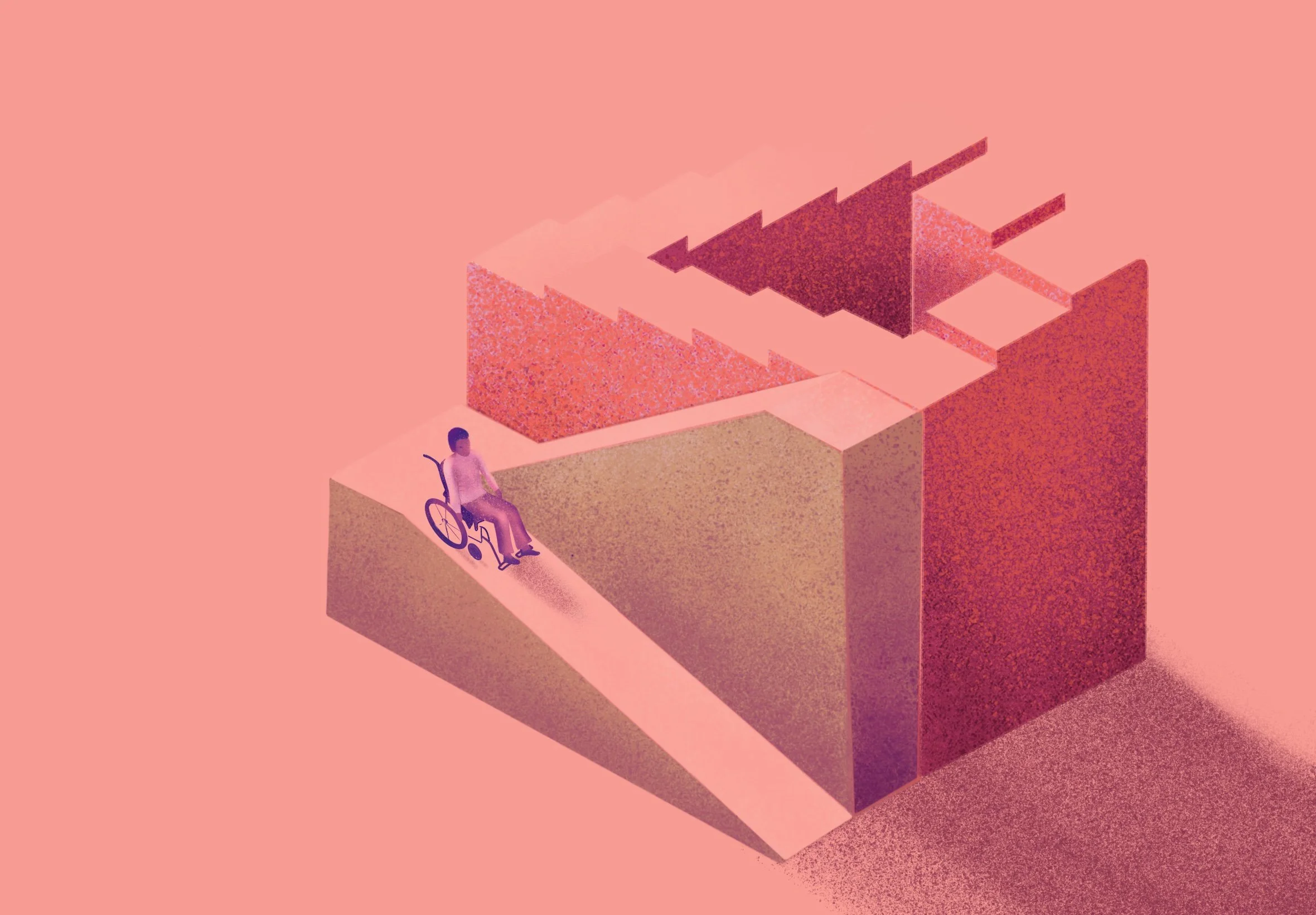

The Social Model of Disability

What role does society play in creating disabling circumstances?

Image credit: Tara Holley

by Kathryn J. McCullough

January 18, 2022

Imagine a row of historic buildings with ornate, concrete facades; housed inside are collections of vertically stacked workspaces, home to local businesses and law firms. In the lunchtime rush, clients climb the stone steps toward the entrance of each building as they hurry to their respective appointments. Amid the bustle, a woman, whose body is paralyzed from the waist down, stops her motorized wheelchair outside the fourth edifice in the historic lineup. Seeing no wheelchair ramp, she stares at the entrance, unsure how to enter the building to meet with her lawyer.

For this woman, what creates the disabling circumstance? Is it her physical state, or is it the building that boasts carefully preserved stone steps but no wheelchair ramp?

The answer depends on the lens through which we view the situation. Scholars have created various models that offer different ways to examine the nature of disability. The medical model, considered a standard due to its predominance, regards disability as an impairment or deficit that resides in the individual, not the circumstances they encounter. For our hypothetical woman in a wheelchair, unsure how to reach her lawyer’s office, the medical model views her impaired mobility as the cause of her disability. In other words, her inability to climb stairs is why she cannot access the building.

As a result, the medical model focuses on fixing the person and their impairments to achieve a level of perceived normal function through medical intervention or rehabilitation. The responsibility falls on the individual to adapt to the immutable world around them. For the woman in our scenario, she must decide how, or if, she is to enter a building not constructed for wheelchair access.

“The social model makes a distinction between impairment and disability.”

Early medical models focused on quality-of-life outcomes, according to a 2016 study published in Public Health Research. But it was rare for the models to account for environment, opportunity, or disabling process since “the focus tended to be on individual conditions, with little attempt to explore how disability could be socially generated,” wrote the authors.

Within a global population of roughly 7.8 billion, one billion live with a disability, and that number continues to increase due to factors such as aging and chronic illness. In the United States, one in four adults lives with a disability, where mobility, cognition, and difficulty with independent living constitute the top three disability types. Given the prevalence and diversity of disability, we must consider a model that extends beyond the individual.

The social model of disability offers such an extension. It shifts the focus from the individual to society’s role in creating disabling barriers and circumstances.

The social model makes a distinction between impairment and disability, according to Tom Shakespeare, a professor of disability research at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, in a chapter he authored in the 2006 edition of The Disability Studies Reader. Impairments are specific to the individual and may occur along a spectrum within the mind or body. By contrast, disabilities are structural, public, and create disabling circumstances for those with impairments. According to the social model, a person’s impairment only becomes a disability when they encounter a societal barrier. In our example of the woman using a wheelchair, the social model considers her paralysis a mobility impairment. She becomes disabled when she encounters the absence of a ramp to her lawyer’s office building.

The power of the social model lies in its mandate for “barrier removal, antidiscrimination legislation, independent living, and other responses to social oppression. From a disability rights perspective, social model approaches are progressive, medical model approaches are reactionary,” wrote Shakespeare. A strength of the social model, said Shakespeare, is its progressive approach, which challenges individual, societal, and legal perceptions of what we consider to be a disability.

United Nations map showing signatories to the Convention. Click on image to enlarge it.

Image credit: United Nations

In a testament to the social model’s transformative potential, a 2020 paper in The International Journal of Human Rights acknowledges the model’s influence in creating the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Adopted in 2006, the Convention is “the first comprehensive human rights treaty of the twenty-first century,” according to the United Nations, and it “adopts a broad categorization of persons with disabilities and reaffirms that all persons with all types of disabilities must enjoy all human rights and fundamental freedoms.”

In 2008, the Convention became a legally enforceable treaty in 182 participatory countries. That year, the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities—an elected body of independent disability experts—was established to monitor the global implementation of the Convention. The 2020 paper noted the Committee’s call for Canada to adopt public campaigns and programs that recognize and reinforce the human dignity and value of all autistic persons and their inclusion in society. By challenging Canada to address the subtle and pervasive ways that public perceptions and language contribute to disabling circumstances and attitudes, the Convention holds society—not the individual—responsible for removing these barriers.

As we continue to examine the world around us and work to develop equitable and comprehensive social policy, the social model of disability offers a foundation on which to create a society that guarantees equal rights, inclusion, and opportunity for people with impairments.

Kathryn J. McCullough

Kathryn J. McCullough is a Tennessee-based science writer and editor and a graduate student in the Johns Hopkins University Science Writing Program. While she writes about cutting-edge biomedical research by day, she lets her passion for the social sciences guide her personal writing projects. She describes her approach as grounded by words and inspired by science.