Re-excavating the Baron’s Bounty

A century-old collection reveals thousands of fossils from now-inaccessible sites

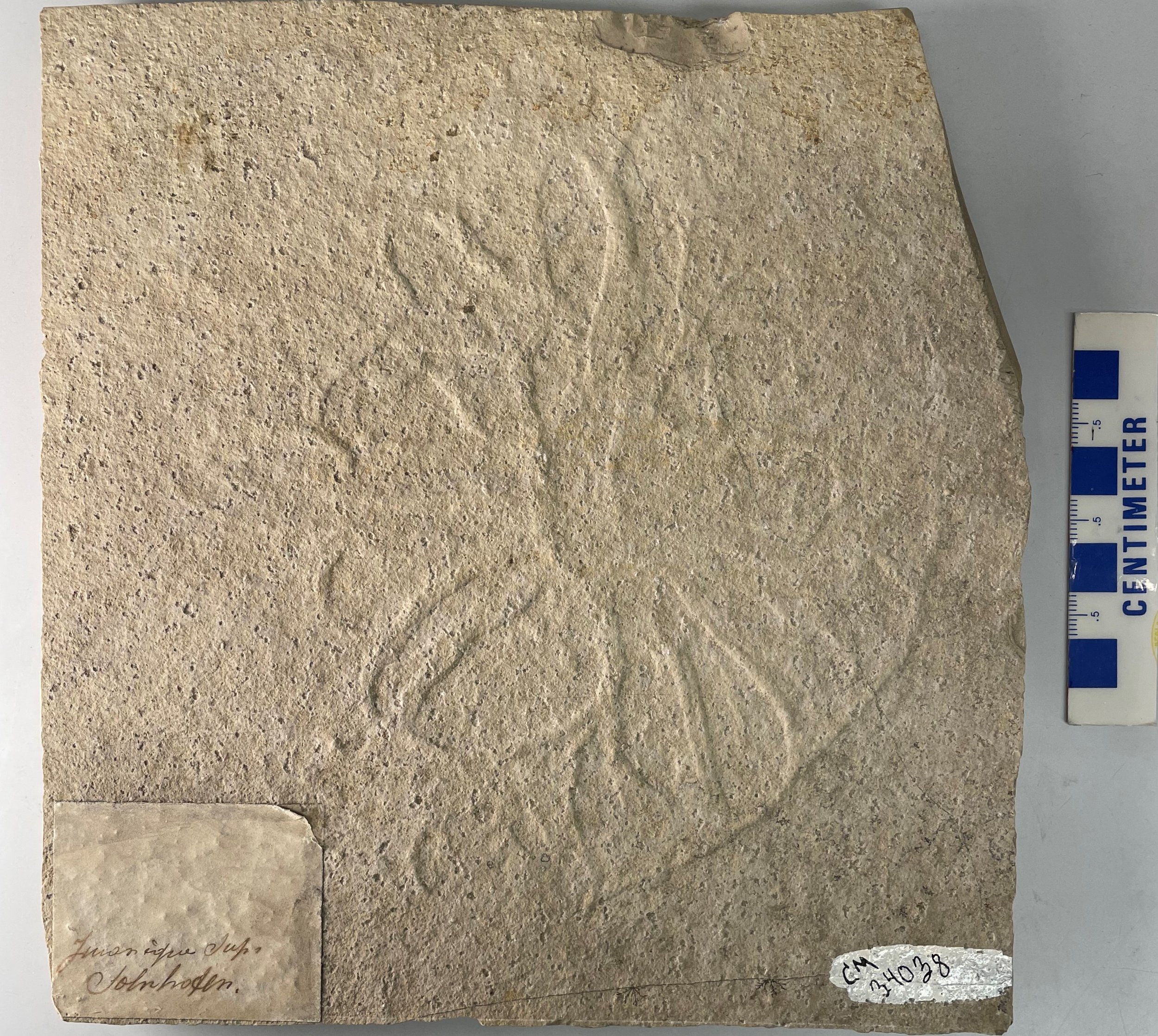

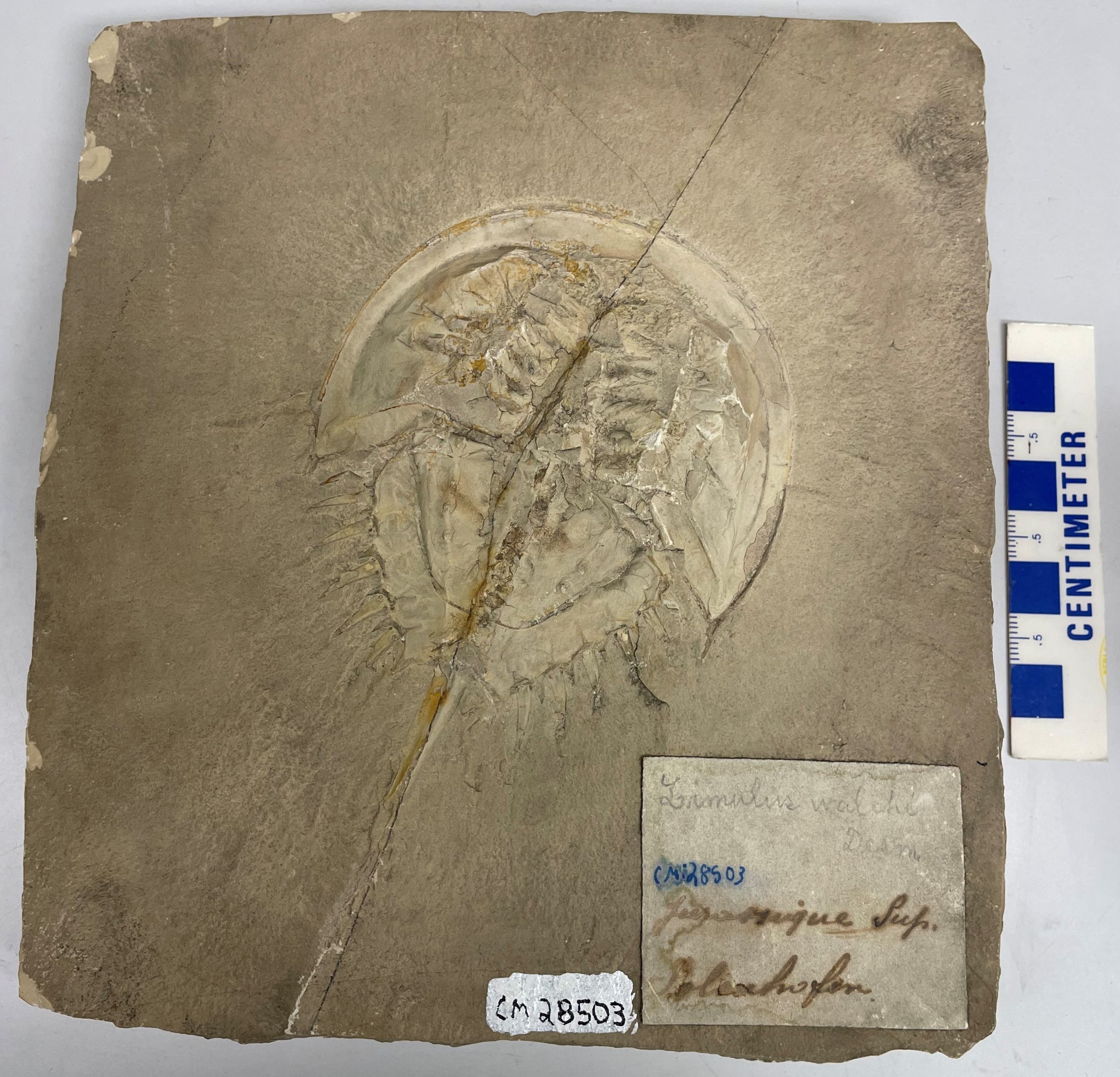

Fossil shrimp, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Image credit: James St. John via Flickr

by Jack Tamisiea

January 18, 2022

In the recesses of Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Natural History, paleontologist Albert Kollar opened a drawer to reveal the petrified inhabitants of a Jurassic lagoon. With a steady hand, he unloaded fossilized sea stars and dragonflies, each more meticulously preserved than the last. Finally, he found the specimen he’d been looking for: the ghostly halo of an approximately 150-million-year-old jellyfish, delicately imprinted on a slab of stone. In all likelihood, it represented a species new to science. But at that moment, Kollar was more interested in the label. Although barely legible after nearly a century of storage, the smudge of the collector’s signature still remained.

Over 130,000 specimens in the Carnegie’s collection possess similarly faded labels. Each denotes some connection with Baron Ernest de Bayet, a Belgian diplomat and prodigious fossil collector. In the late 19th century, he accumulated what many paleontologists deemed the greatest private fossil assemblage in the world. When it went to auction in 1903, it took a king’s ransom from Andrew Carnegie to secure it for his namesake museum in Pittsburgh.

A century later, Kollar, the museum’s collection manager for invertebrate paleontology, said he believes he and his predecessors have only scratched the surface exploring what Carnegie purchased. A small fraction of the collection has been on display since 1907, but the majority remains off-exhibit, entombed in drawers and crammed into boxes. No one is quite sure exactly how many specimens the museum purchased from Bayet, how many known species are represented, and how many new species are hiding in plain sight, waiting to be discovered.

“The scope of the Bayet collection is substantial in its diversity,” Kollar said during a recent tour of the collection. As historic fossil sites disappear, and a growing number of species succumb to extinction, he said he believes that this fossil collection has only become more valuable to the scientific world. “These [fossils] are relevant to studies on taxonomy, extinctions, climate change, and ecological changes over the Phanerozoic Eon,” Kollar said, referring to the last 540 million years of life on Earth. To reach these insights, Kollar and a team of volunteers have begun an ambitious effort to catalog the uncharted depths of Bayet’s fossilized bounty.

In 1902, Bayet had assembled his masterpiece collection. As a Belgian nobleman, Bayet had the necessary means and connections to pursue one of the trendiest gentleman hobbies of the day: fossil collecting. The field of paleontology was in its infancy, and Bayet ravenously stockpiled any fossil he could get his hands on. After decades of trading, buying, and selling, Bayet’s collection was deemed by many as the most comprehensive collection of fossils outside the great museums of Europe. Some, like British paleontologist Arthur Smith Woodward, went a step further, pronouncing to the Pittsburgh Dispatch in 1903 that the “de Bayet Collection [was] the most perfect gathering of extinct animals and plants of Europe ever assembled.”

Bayet had scoured Europe for some of the most well-preserved vertebrate remains yet discovered, establishing a fossilized menagerie containing everything from giant stingrays to flying reptiles known as pterosaurs. The New York Times’s 1903 summation of the Bayet collection’s highlights sounds like an absurd roll call right out of a Dr. Seuss book: “There are giant crocodiles from Italy, giant tortoises, fish-lizards, bird-lizards…and other denizens of the world before man which have received names as hard as their looks.”

However, the bulk of Bayet’s prized collection consisted of creatures without backbones, harvested from many of Europe’s most famous fossil sites. From Jurassic rocks along England’s Lyme Regis coast, he procured curled nautiluses and petrified crinoids, an echinoderm whose fossils look like a bouquet of quills baked in a kiln. He stockpiled 45-million-year-old clams and brachiopods from the outskirts of Paris and mustard-colored trilobites from 500-million-year-old outcrops in what is now the Czech Republic.

However, his most lucrative collecting spots were the limestone beds near Solnhofen, Germany. One hundred fifty million years ago, the site was covered by a network of shallow, sheltered lagoons. When animals died here, they sank to the sandy bottom, where anoxic conditions deterred scavengers and delayed decay, which preserved delicate soft tissue. As a result, groundbreaking finds like Archaeopteryx feathers and pterosaur wings appear on the rock in stunning detail. Bayet was particularly fond of the site’s ultra-rare imprints of soft-bodied jellyfish, squid, and other rarely preserved invertebrates.

All of these remarkable fossils did not come cheap, however, and by 1902, Bayet’s extravagant fossil purchases had caught up with him. And, perhaps even more financially draining, he was in love. Eager to please his new wife, Bayet decided to part ways with his prized collection to purchase a chalet on the shores of Italy’s Lake Como.

“You can’t get to this stuff anymore, so it does hold a great scientific significance.”

When his collection landed on the auction block, it sent ripples throughout the burgeoning field of paleontology. Museums on both sides of the pond, including Woodward’s renowned British Museum, wanted a piece, sparking a tumultuous bidding war. As more and more museums entered the fray, it appeared only a king’s ransom could secure the collection.

Amongst so many venerated institutions, William Holland may have seemed like a long shot to secure such a paleontological prize. A Presbyterian pastor and the former chancellor of the University of Pittsburgh, Holland had only recently been hired to direct the fledgling Carnegie Museum. However, while the museum’s scientific stature paled in comparison to European museums, it did have the financial backing of its namesake, Andrew Carnegie, who was the freshly minted richest man in the world after selling his steel company to J.P. Morgan.

Carnegie was no stranger to spending big on fossils. In 1899, he financed an expedition to the badlands of Wyoming to exhume the titanic Jurassic sauropod Diplodocus carnegii. When he viewed the enormous centerpiece of his museum in an essentially empty hall, he directed Holland to dispatch more fossil hunters to Utah. When Holland heard Bayet’s collection was for sale, he immediately thought of Carnegie’s demand for more dinosaurs, according to Kollar. Although the collection lacked giant reptiles, he saw the vast assemblage of marine species as the perfect complement to the terrestrial fossils arriving from the West.

By the summer of 1903, Bayet’s asking price had risen to an astronomical $25,000 (well over $785,000 today). Unfazed, Carnegie sent Holland to Europe with a $25,000 check, more than the museum’s entire annual budget. Later, Holland wrote to Carnegie, “We are never likely to have another such chance, and you have done a most splendid thing in securing [the Bayet Collection] for our Museum of Paleontology.”

Purchasing the fossils turned out to be the easy part; Holland was able to negotiate Bayet down to under $21,000. However, shipping his collection back to Pittsburgh proved to be an ordeal. It took three weeks to pack each of the 130,000 fossils into nearly 260 crates. When the shipment arrived in Pittsburgh in September of 1903, Holland was met with another predicament: the museum was too small to house them all. Without even unpacking most of this fossiliferous fortune, Holland moved the crates to a nearby warehouse. After spending tens of millions of years in the ground, it appeared the fossils would have to bide their time in storage for a few more years as Carnegie constructed a new museum building.

Just two months later, all was nearly lost. On December 29, 1903, a fire raged through the warehouse, threatening to incinerate Bayet’s collection. Devastated, Holland wrote the following day that the collection was “destined to go up in smoke.” However, on December 30, the Pittsburgh Daily Post declared in bold letters on its front page, “RARE FOSSILS MAY BE SAVED.” Firefighters had arrived just in time to quell the flames before they reached the crates. Ironically, the water used to fight the fire caused more damage to the fossils. Several of the soaked cuttlefish specimens were stained purple, the result of water awakening ancient ink sacs.

Crisis averted, Holland now faced the task of sorting through Bayet’s sprawling collection. In the early days, the museum’s paleontologists scrawled arduous Latin names like Paradoxides spinosus into massive ledgers. However, generations of scientists only made a dent in the impenetrable collection. Today these ledgers, like the fossils described within their pages, remain in Carnegie's basement, gathering dust.

Joann Wilson with fossil trilobite Paradoxides spinosus from the Baron de Bayet collection.

Image credit: Carnegie Museum of Natural History, with permission from Joann Wilson.

Like a lucrative investment, the Bayet fossils continue to rack up scientific interest more than a century after they arrived in Pittsburgh. As one of the premier fossil collectors working during the infancy of paleontology, Bayet had access to several of the historic European sites that would define entire geological epochs. As Europe industrialized over the next century, many of those classic sites were picked dry, destructively mined, or filled in entirely to make way for human settlement.

“You can’t get to this stuff anymore, so it does hold a great scientific significance,” said Jessica Cundiff, the collection manager of invertebrate paleontology at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. “We have material that no one can ever go and collect again because the localities are no longer accessible.”

Since the beginning of the pandemic, Cundiff said, she’d been pouring through Harvard’s archives to learn more about the scientists whose collections helped launch the department in the late 19th century. Like the Carnegie Museum, the backbone of Harvard’s invertebrate paleontology collection is a diverse assemblage of fossils found throughout Europe’s most important geologic sites. For locales like Germany’s Solnhofen quarry, the holdings at Harvard essentially mirror those Bayet sold to Carnegie.

In fact, some specimens are even plastered with the same labels, tying them to a single collector of origin. “I see the photograph of the trilobite from the Czech Republic and think, ‘You have some of the same stuff that we have!’” Cundiff said over a recent Zoom call. “That’s one of the benefits of spending the time to catalog—not only do the researchers know you have it and can use it, but it could be a resource for any other museum collection that might have the same specimens.”

Because of the Bayet specimens’ growing scientific value, Kollar said he was working to bring them into the digital age. His ultimate goal, he said, is to load the information from each specimen’s faded label into a database where researchers at other museums can access crucial information, like species and locality, with just a few taps of their keyboard.

While the process may seem straightforward, Kollar and a few volunteers must wade through the mire of past attempts to catalog the Bayet material. Each curator had their own system and entered their data in different places, making the task of uniting all these various catalogs akin to translating a curatorial Tower of Babel. Kollar was not even sure how many specimens they’d need to examine. “This 130,000 number is really an unknown number because it has never been counted,” he said. The number of specimens seemed so indomitable that no one even attempted to count it all. “Decades after I started, we finally have an opportunity to fully understand what we have,” he said.

However, counting and cataloging the specimens is only one of his goals, Kollar said. In addition to the massive haul of specimens, Holland also received a mountain of letters and fossil lists. Joann Wilson, a volunteer in the Carnegie Museum’s Section of Invertebrate Paleontology, said she was attempting to sift through these correspondences in an effort to place Bayet’s fossils in context. “It’s almost like detective work, which I love,” she said. Oftentimes, said Wilson, she has to work back from the specimen’s label, which is like a collector’s fingerprint—each collector attached his own, unique label to a particular specimen before it found its way to Bayet. Once Wilson and Kollar link a particular label to a collector, she said, they then rummage through the archives to learn more about the collector.

While Wilson said she believes further explorations of the archives will continue to flesh out the collectors who bought and sold them, she also hopes to shed light on the other individuals involved with excavating these fossils. Like many sciences, paleontology has long been mired by colonialism and exploitation. Nowhere is that more apparent than in the aristocratic world of 19th-century collectors like Bayet. While scientists praised his expansive collection, the laborers and indigenous people behind the discoveries of those specimens were forgotten, lost to time like the fossils Bayet coveted.

“As you’re parsing out the words, there’s a lot to learn about the times, about the different individuals, a lot of whom don’t get talked about,” said Wilson. “One of my goals is to find those stories.”

It seems like the more Kollar and Wilson uncover, the more unknowns they encounter. Paleontologists who have visited the collection salivate over the assortment of new species hiding for decades in the Carnegie Museum’s basement. Almost every drawer is filled with scientific mysteries, from the delicate etchings of Solnhofen sea jellies to the rigid shells of Belgian brachiopods.

“In all probability, many new species will be discovered once the new catalog is completed,” said Kollar. “It’s a tremendous story that hasn’t been told.”

Jack Tamisiea

Jack Tamisiea is a Chicago-based science writer who covers natural history and environmental issues. In addition to The Science Writer, his work has appeared in National Geographic, Scientific American, Hakai Magazine, The Atlantic, The New York Times, and others.