Download a Hand

How an open-source 3-D-printing community is inspiring a new generation of low-cost prosthetic limbs

A child uses her prosthesis as she gets tape from a tape dispenser as Jorge M. Zuniga and his team run her through a series of tests on Wednesday, Jan. 15, 2020, in Omaha, Nebraska, at the child's home. Image credit: Jorge Zuniga, University of Nebraska at Omaha

by Jayne Williamson-Lee

January 18, 2022

In 2014, prosthetics designer Jorge Zuniga was honing ideas for a new artificial hand when his son came to him with a drawing he’d done. It was of a large, metal-armored glove with screws acting as joints where the fingers naturally bend—an aesthetic departure from other prosthetic hands Zuniga had seen on the market.

At the time, designers were trying to make prosthetics that looked just like human hands, said Zuniga, an assistant professor of biomechanics at the University of Nebraska Omaha. “My son gave me the idea of a robotic hand.”

Zuniga began building on his son’s concept, creating what he would later call the Cyborg Beast, a low-cost prosthetic hand that can be 3-D printed to assist adults and children with upper-limb differences. “We posted the 3-D-printing files online, and they were super, super popular,” he said.

The Cyborg Beast, created by Zuniga and his designer colleagues, is one artificial hand in a line of upper-limb prosthetic devices born out of Enabling the Future (commonly known as e-NABLE), an online, open-source movement of volunteers who design and deliver free and low-cost 3-D-printed prosthetics for adults and children who are missing fingers and hands. The community, now spanning 100 countries, has served as a bedrock of innovation, inspiring new designs in the prosthetics industry. The wide accessibility of 3-D printers and 3-D-file-sharing websites like Thingiverse has also opened the possibility for this kind of innovation. For prosthetics designers like Zuniga, who are constantly tailoring and fitting new devices on their clients, particularly children, 3-D printing has also proved a necessary tool.

A child throws a ball to Jorge M. Zuniga using her prosthesis as she is run through a series of tests on Wednesday, Jan. 15, 2020, in Omaha, Nebraska, at the child's home. To the right is graduate assistant Kaitlin F. Image credit: Jorge Zuniga, University of Nebraska, Omaha

When it comes to being fitted with a new hand, younger children face a different set of challenges than adults, which 3-D printing has helped address, said Zuniga. While adults care more about the function of an artificial limb, children are initially more concerned about its appearance, which may determine whether they try it out. 3-D-printed solutions offer a wider array of customizable features, such as colors, than what the industry offers, and trying them all out will not cost thousands of dollars. “You can print four or five versions of the same device in one day,” Zuniga said.

Ananya Mukundan with a printed arm. Image credit: Ananya Mukundan

To create a new prosthetic hand, Zuniga first gets a child’s limb measurements in person or from a photo. He then creates a 3-D model of their limb using specialized computer graphics software. The model includes different components of a hand—the wrist, palm, fingers, and pins to connect the various parts—which Zuniga exports as individual pieces into a new file type compatible with a 3-D printer. These files are sometimes called mesh files for how they appear on a computer screen—in Zuniga’s case, like a hand wearing a mesh glove. A 3-D printer follows these mesh lines to make the shape of the hand.

As it prints, the 3-D printer views the hand as “a series of two-dimensional drawings stacked on top of each other,” said Frankie Flood, a studio art associate professor at Appalachian State University. Flood became involved with Enabling the Future when a woman approached him about creating a hand for her daughter, who was born without fingers on her right hand.

To convey to his students how an object is 3-D printed, Flood said he uses the example of printing a hypothetical loaf of bread. The printer would begin with the crust at one end of the loaf, first printing the perimeter of a bread slice and then filling in its center. “Then [the printer] would raise up and print the outline of the crust of the second piece and then infill that,” explained Flood.

This type of 3-D printing is called fused deposition modeling (FDM), and it resembles “a very precise hot-glue gun,” said Richard Luttrell, an Enabling the Future community member and owner of a 3-D-printing business. Most FDM 3-D printers use two materials, a modeling material that makes up the object being printed and a support material that holds up the various pieces as they are being printed. These materials come in the form of plastic threads, or thermoplastic filaments, which are fed through the printer’s nozzle, or “hot end,” as Flood called it, because of how the nozzle heats the plastic threads to their melting point. As the melted plastic coming out of the nozzle cools and hardens, it fuses on top of the printer’s build platform or other present material to create the printed object. Once the nozzle completes a “slice,” or cross section of the object, the printer lowers its build platform to make room for the next layer, repeating the cycle until the print is complete.

Ananya Mukundan, a high school senior in Union City, California, saw that a 3-D printer was collecting dust in one of her teacher’s classrooms. When her teacher told her that it could be used to print someone a hand, Mukundan volunteered to run the school’s Enabling the Future chapter. The organization’s volunteers can connect with people with limb differences through its website forum, and from there, build them one-of-a-kind prosthetics.

That’s how Mukundan found “Noah,” an elementary school-aged boy who was born without a hand but had part of a residual palm. In his post on the Enabling the Future forum, Noah said he wanted to ride his mountain bike, but gripping the handlebars had given him a rubber burn. Using Noah’s limb measurements, Mukundan and her team printed him a hand with fingers by customizing a ready-made design, called the Phoenix Hand v3, from Enabling the Future. In the file’s original form, Noah would not have been able to put his limb into the glove if Mukundan had printed it as is. To adapt it for Noah, Mukundan and her team adjusted the model by widening the palm to fit his limb inside.

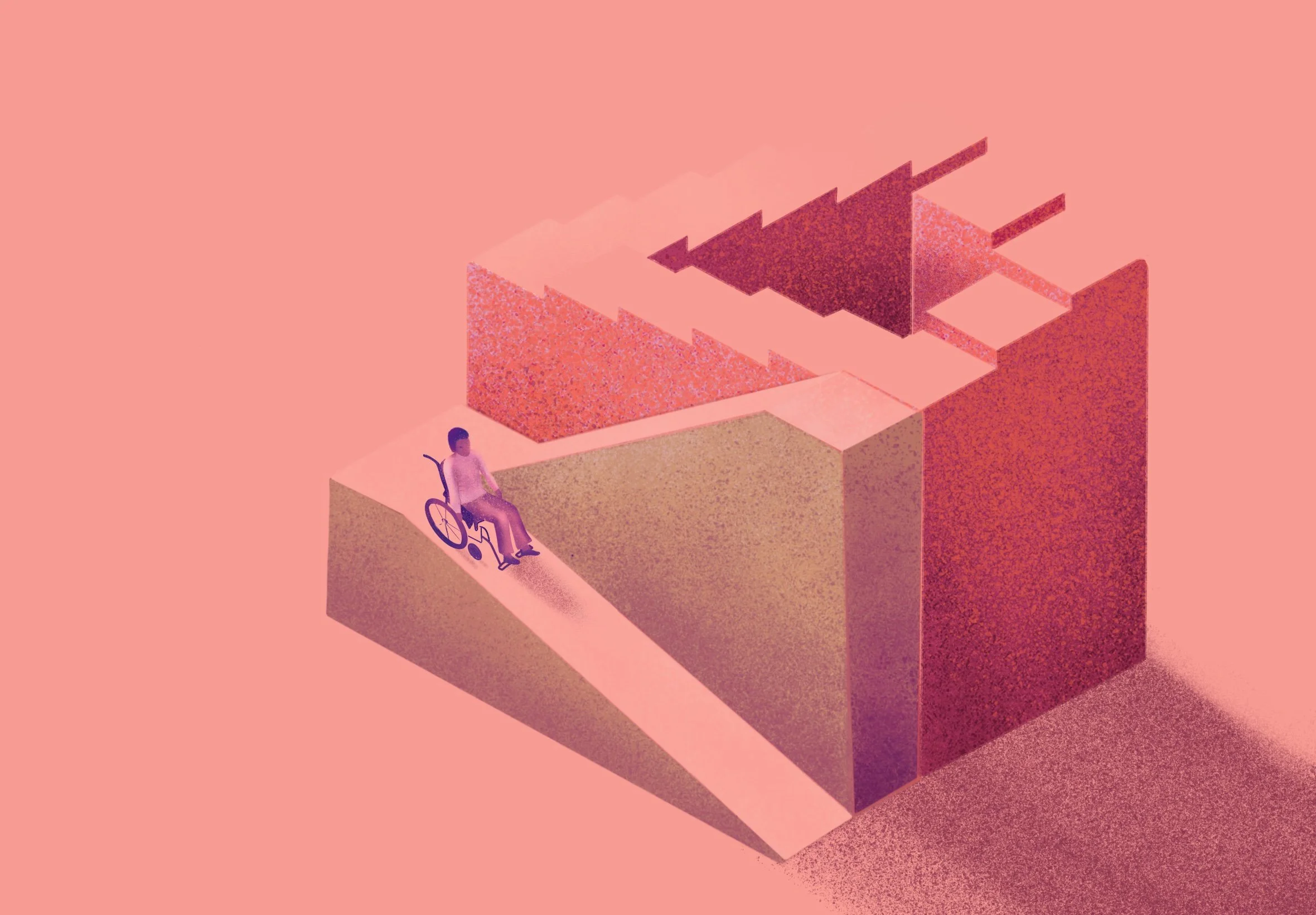

While the Enabling the Future community has provided many individuals with access to low-cost prosthetic devices that suit their needs, challenges remain with helping children fully adopt and accept prostheses as extensions of themselves. Children are also less likely to embrace a prosthetic that doesn’t resemble a human hand. Though Zuniga’s son put forth a unique robotic-hand design, he drew it as having five fingers. Many Enabling the Future designs have stayed true to the shape of the human hand, though they can’t imitate the complex movements of the hand. All fingers on the Cyborg Beast, for instance, move in unison based on a pulley system initiated by flexing one’s wrist, which allows the device to grasp an object.

Getting children a new limb they like is just half the battle, as many abandon their prosthetics after a period of time. Through his research, Zuniga has tried to understand why. “If you’re born with a [limb] deficiency, you [might not] have the neural wiring required to use those fingers because you never had [fingers],” he speculated. “That may be the reason, but we’re not sure.” Other studies have reported high rates of prosthesis rejection. One 25-year scoping review found that one out of five people with upper-limb differences rejects their prosthesis due to a lack of durability or function.

Albert Manero, co-founder and president of Limbitless Solutions, a nonprofit organization at the University of Central Florida that creates bionic arms for children at no cost, is working to help children continue using their prosthetics once the novelty wears off. Using an app that pairs with prosthetic devices, children can play video games designed to train them to use their new hand or arm.

Manero compared using a new prosthetic to learning how to play an instrument. “There’s always going to be this time where you’re playing the instrument, and the noise coming out of it doesn’t sound the way you want it to,” he said. “It’s the same way for the prosthetic—you’re putting energy into it to be able to make it do what you want. But it takes time . . . to get it to be really fluid.”

When Mukundan and her fellow high school volunteers finished customizing Noah’s new hand, they printed it and shipped it off to him. With the new prosthetic, Noah could pick up toy trucks, hold the handlebar of the bike he always wanted to ride, and even throw a football. Mukundan said his parents texted her and her team that it was “the best gift that he’d ever gotten.”

Jayne Williamson-Lee

Jayne Williamson-Lee is a health and technology writer based in Denver. Her work has appeared in Psychology Today, Mashable, OneZero, and others.