Security at Stake

Where will we go to escape climate danger?

Image credit: Tara Holley, using elements from Unsplash

by Anna Marie Zorn

January 18, 2022

One-hundred and sixty-two million Americans—one in two—will likely be at risk of crisis-level heat and drought within the next 50 years. For more than half of them, these climate changes will probably be severe. Globally, that number is estimated to reach 3.5 billion.

Wildfires rage in the West as hurricanes howl from coastal waters. Flash floods wipe out mountainsides in Tennessee, and sea levels continue to rise around island nations. It seems like there’s nowhere safe to go. But some US cities, positioning themselves as climate refuge cities where citizens can find safety from the burgeoning climate crisis, may offer a potential sanctuary. From so-called climate-proof Duluth, Minnesota, to Buffalo, New York, cities are marketing themselves as havens where citizens can escape the worst threats of climate change.

Humans, like any species, require a precise environmental niche in which to live, and the “human climate niche” has been a relatively small area of the Earth for the last 6,000 years, according to research published by Chi Xu and colleagues in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. In the face of impending climate change, however, many humans may be forced to migrate. Though refuge cities might offer certain benefits, nowhere on Earth is climate-proof.

To qualify as refuge cities, they must meet a few basic requirements: a stable water supply, temperatures that don't fluctuate too greatly, and adequate infrastructure. Bearing all that in mind, it will be interesting to see whether any city, regardless of marketing, becomes a true climate refuge.

Stable Water Supply

Cities like Duluth, situated along Lake Superior in the Great Lakes region, seem to fit the bill when it comes to water supply. Lake Superior, with its 3 quadrillion gallons of fresh water, is the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface area and the third largest by volume. The common expression of Minnesotans is, “If you poured out Lake Superior, it would cover North and South America under a foot of water.” But bodies of water like lakes are finicky and subject to fluctuations in evaporation and precipitation. In fact, experts have seen Lake Superior’s levels hit both record highs and lows within the past 15 years.

Less volatile options than aboveground reserves are aquifers—underground water sources.

“Providing groundwater access to people is going to be really important,” said Nick Simpson, the lead author on an upcoming chapter of the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report. Aquifers, being less susceptible to fluctuations from weather shifts and changing climate patterns, tend to offer a steadier and more reliable water source. However, climate change may still impact aquifers, including the quality and quantity of groundwater supply.

This is, in part, thanks to the warming temperatures seen from rising greenhouse gas emissions.

“In terms of the hydrological cycle, climate change can affect the amounts of soil infiltration, deeper percolation, and hence groundwater recharge,” wrote Wen-Ying Wu in a July 2020 study about the impact of climate change on groundwater supply. In other words, with warmer temperatures, water might not be able to penetrate as deeply into the soil to be stored in underground aquifers. Warmer temperatures drive more evaporation, leaving less surface water available to filter underground in the first place.

Steady Temperature

In the summer of 2021, a heatwave settled over the Pacific Northwest, creating a heat dome; warm air tried to rise and, finding nowhere to go, stagnated before being forced down by more rising air. This lasted for about a week and taught a valuable lesson: even humans in affluent areas with access to air conditioning and modern infrastructure are vulnerable to the effects of heat. Current excess death tolls suggest there were about 800-1,200 more deaths than typical in both Canada and the US. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, heat is, on average, the deadliest weather-related killer in the US (barring some outlier events like Hurricane Katrina). Climate refuge cities would need to be in areas where severe, long-lasting heat waves would not likely occur since severe heat waves contribute to crop failure, wildfires, and drought conditions.

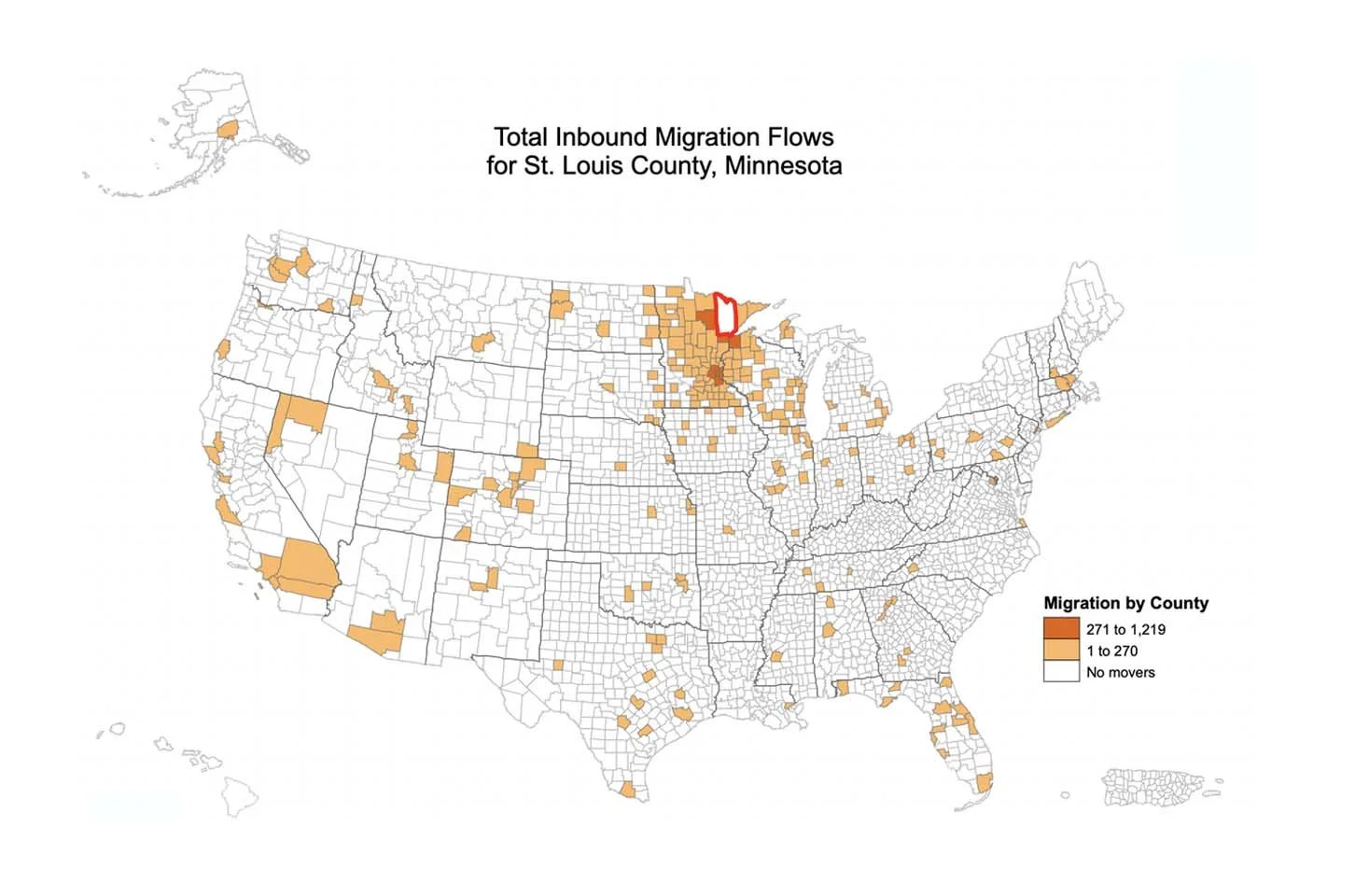

Just looking at vulnerability to heat, self-proclaimed refuge cities like Buffalo and Duluth do seem like safe havens. But they still would have very cold, very long winters. Temperatures in Duluth can fall below minus 20 degrees Fahrenheit during the coldest months. So it’s no surprise that, according to US Census Bureau data, many people are still moving to the “sunbelt” of the US, where water is scarce, heat bakes the land, sea-level rise threatens, but the sun almost always shines.

Over 12,000 people moved to the county where Duluth is located in the past five years according to the American Community Survey, 2015-2019. Image credit: US Census Bureau

Adequate Infrastructure

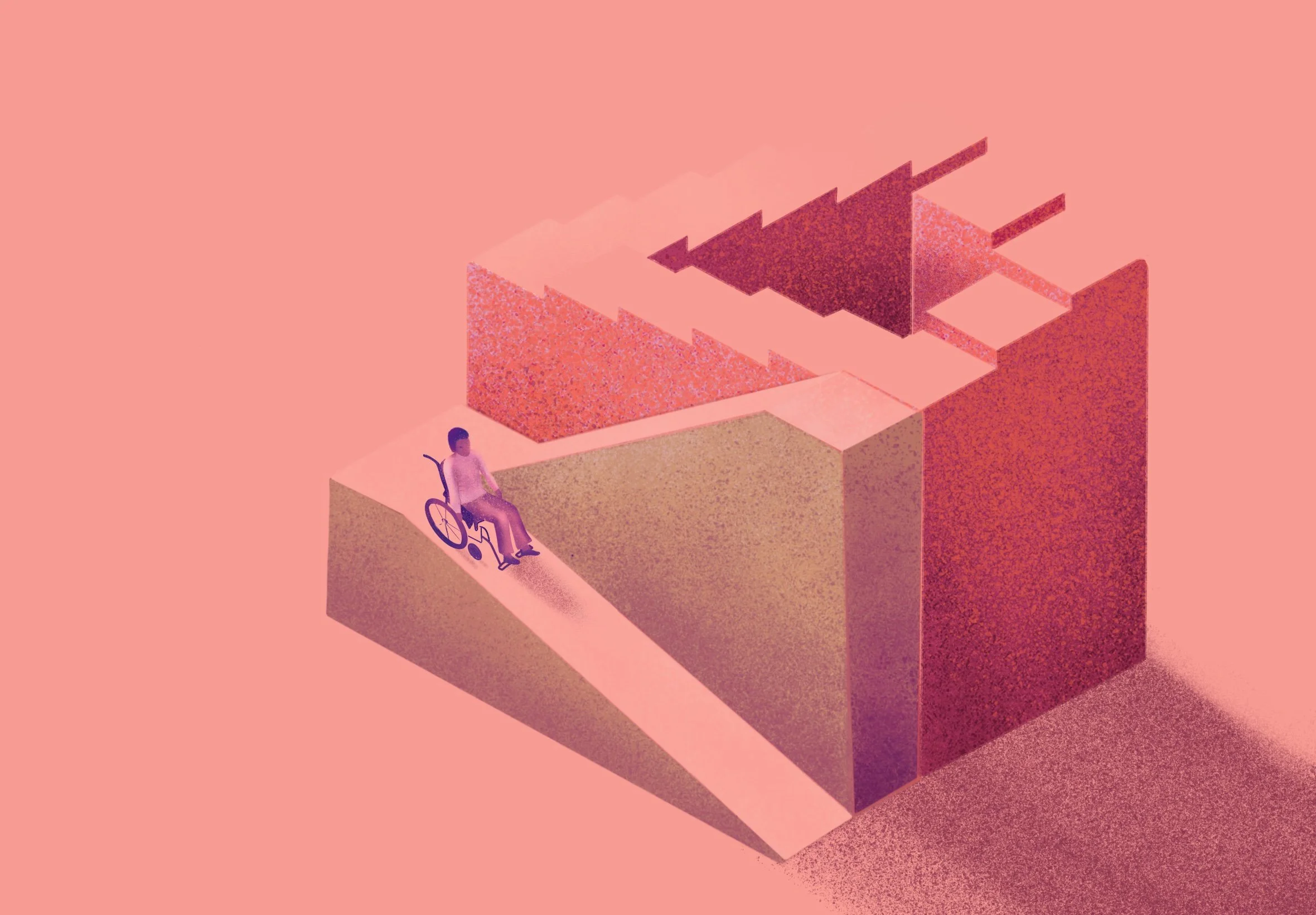

In the Great Lakes area, where cities like Duluth promise refuge, infrastructure is often old, outdated, and unable to accommodate the increased inches of rainfall that are expected as climate change continues. As factory jobs moved and workers left, many of the cities situated along the Great Lakes shorelines fell into disrepair. Abandoned buildings, roads, and sewage systems aged and suffered neglect. On one hand, this means that there is plenty of opportunity for repopulating these areas and for growth. On the other hand, without enough people to pay for improvements before climate refugees arrive, these cities might not be able to accommodate new arrivals.

New arrivals mean more strain on outdated systems. Rundown areas would be more susceptible to flooding since the drainage systems cannot handle increased demand. Rainfall overburdens outdated sewer systems, leading to sewage contamination. This situation also poses an immediate threat because, according to the Fourth National Climate Assessment, extreme precipitation events—defined as those above the 99th percentile of daily precipitation values—increased by 42% between 1958 and 2016 in the Midwest and will continue to increase. Cities like Duluth or Buffalo may not be able to accommodate new demand on their infrastructures without incentivizing improvements first. Some progressive cities in the region, like Detroit, have begun green infrastructure initiatives. Turning open spaces like parking lots into garden reservoirs helps flood management and prevents surface level heat from rising in asphalt and cement-covered cities.

Refuge Cities: The Bottom Line

Without major mitigation efforts, Xu et al. predict that several hundred million more people globally will face exposure to climate-related risks and poverty.

“It’s happening now,” said Simpson. “In the Amazon, it’s becoming uninhabitable. There [are] indigenous people in Canada and northern Alaska that are going to struggle to make ends meet based on the traditional livelihoods with loss of ice.” He emphasized the need for cooperation to survive whatever the next generation brings, but he also cautioned against too much hype around refuge cities.

“The talk about refuge cities, it’s a positive, sexy thing of the future,” added Simpson. But he warned that humans have not historically shown a willingness to share resources and said the IPCC has seen a much more individualistic response to climate change in places that have been the most impacted to date. “People who have the means secure access, but there’s not a general sharing of resources.”

So even with investments to secure clean water, relief from the heat, and updated infrastructure, it will likely take a cooperative and group-minded effort to make it possible to find a true climate refuge.

Anna Marie Zorn

Anna Marie Zorn is a freelance science writer based in the greater Milwaukee area. With a degree in biology, she is fascinated by subjects from the molecular to the macro. In her free time, you might find her acting on a community theater stage or bingeing true-crime documentaries.