Lice Lessons Learned

A pediatrician explains everything you never wanted to know about lice

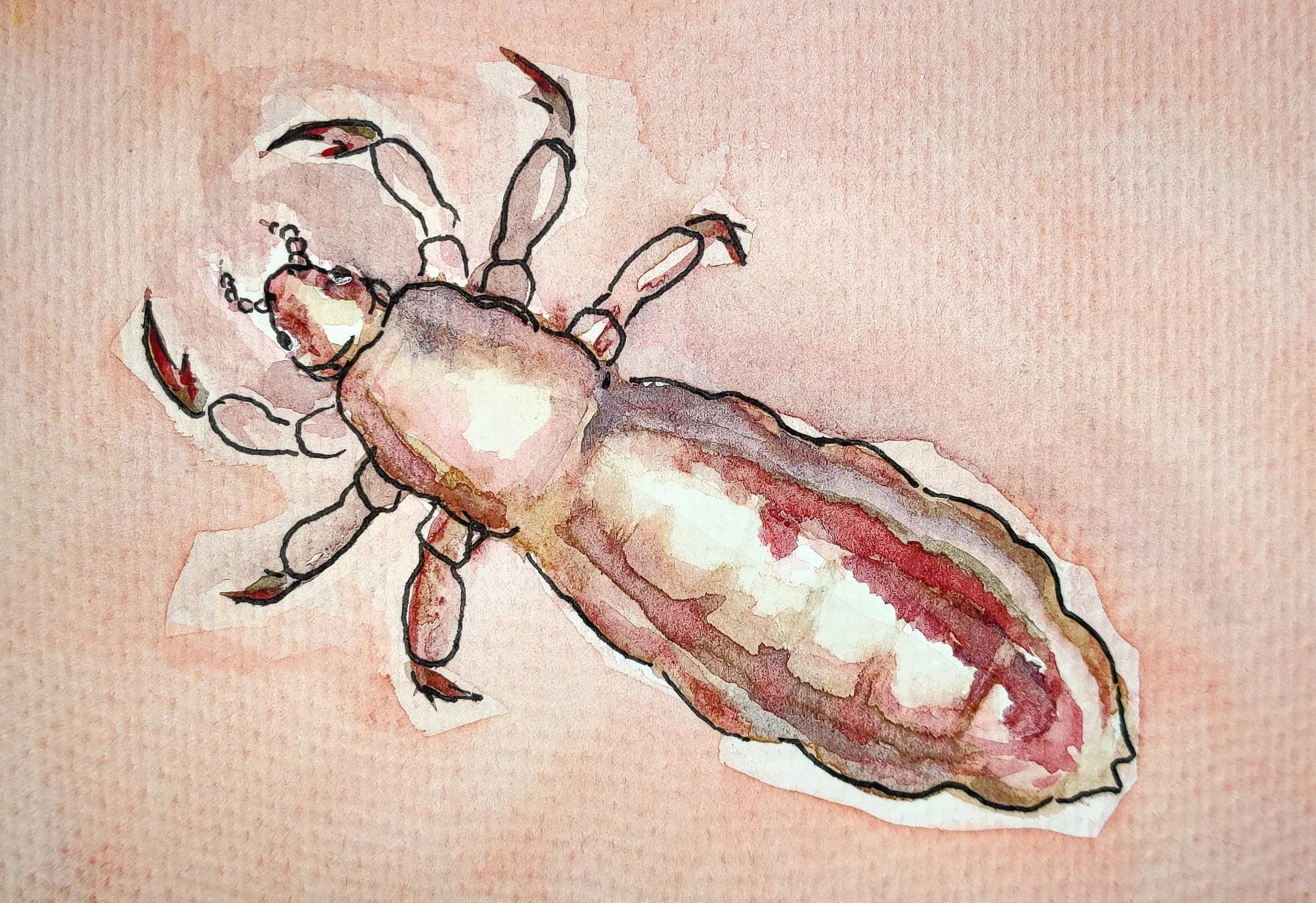

“Once we start thinking about them, lice infest our minds even more effectively than our hair follicles.” Image credit: Watercolor and ink by Veronica Tremblay for The Science Writer

by Sarah Hartnett

December 8, 2024

“Ha! Whaur ye gaun, ye crowlin ferlie?

Your impudence protects you sairly.”

In church a few months ago, I stood helpless as my 7-year-old clawed at his head and wailed, “Itchy!” in the desperate tones of a soul condemned. There is no discreet way to check a scalp in this setting, but I did not need to. I knew the truth. Everybody sitting within a five-pew radius knew the truth. Lice be with you.

Lice are — and always have been — with us. Paleoentomologists can analyze the DNA of prehistoric lice remains found buried with their hosts to help piece together the story of early human migrations. Lice go where we go. Their story is our story.

In 2022, archeologists in Southern Israel excavating the ruins of the ancient city of Lachish found an ivory comb that belonged to a Canaanite who probably lived around 1700 B.C.E. Inscribed with the oldest sentence we have yet discovered, in the oldest alphabet we know — proto-Canaanite phonemes adapted centuries later by the Phoenicians — it reads almost like a prayer: “May this tusk root out the lice of the hair and the beard.”

Amen.

*****

Over 4,900 species of lice exist, each one a highly engineered parasite that can only survive on the host bird or mammal lucky enough to be its evolutionary niche. Some lice bite. Some lice suck, including the three species that call us home: the head louse (Pediculus humanus capitis), the body louse (Pediculus humanus), and the pubic louse (Pthirus pubis).

Many lice now carry a genetic mutation that makes them immune to the most common brands of lice shampoo in American households, and resistance is emerging against even newer treatments. Image credit: Watercolor and ink by Veronica Tremblay for The Science Writer

The head louse and body louse look alike and are closely related, but lead very different lifestyles. Body lice live in the folds of clothes and can transmit serious diseases like typhus. Luckily, they can’t survive a hot-wash laundry cycle, so they are rare outside overcrowded, unhygienic settings. Head lice aren’t known to transmit disease but are unfussy and egalitarian; any human hair suits them just fine. Adults grow to about 3 millimeters, and their slim bodies are often compared to sesame seeds by people who must never want to eat sesame seeds again.

Pubic lice are about half the size of their above-the-belt cousins. Their squat build and sturdy claws earned them the nickname “crabs.” They are spread by direct pubic-hair-to-pubic-hair contact. On rare occasions, they journey north to set up shop in the eyelashes — a fact I would prefer never to think about again, if possible.

But it isn’t possible. Once we start thinking about them, lice infest our minds even more effectively than they do our hair follicles.

*****

Long ago, when I was a shiny new doctor, a patient’s mother presented me with a Ziploc bag full of yellowing dandruff flakes and dead bugs in various stages of desiccation.

“He has lice.” She shook the baggie for emphasis, and the contents spilled onto my desk.

“I see,” I managed. “We’ll get that taken care of.”

Swapping stories with my compatriots, I discovered I am not the only pediatrician to have received such a gift. Some conscientious parents even turn into amateur entomologists, counting and cataloging the lice they capture.

What would compel someone to provide proof of infestation? It may be a fear of not being believed or taken seriously. Maybe they need reassurance that someone understands the gravity of the situation. But nothing drives otherwise rational people to act irrationally, quite like the harmless and ubiquitous head louse.

“Did you hear about these new lice?” another parent once asked, his eyes ablaze. “The ones you can’t even see or feel?”

“I’ll have to look into that,” I replied with practiced diplomacy.

*****

A dentist’s office once called me with a request to update a patient’s medical clearance note because his oral surgery had been canceled and rescheduled. No, he wasn’t sick or anything, they explained. He just couldn’t go into the operating room because he was — shudder — crawling with lice. Pulling decayed teeth, slicing oozing gums, burrowing into infected bone? No problem. Lice? No way.

I have yet to find evidence that lice pose a serious health risk in the operating room, but that doesn’t stop them from wreaking havoc when they turn up uninvited. An article published in the September 2023 issue of the Journal of Orthopedic Case Reports tells the tale of young twins who were scheduled for hip surgery. During the first surgery, the anesthesiologist noticed the child had lice. The surgical team checked the sterile field, found it lice-free, and completed the procedure. But what to do about patient number two? The surgeons sought counsel from an infectious disease specialist, who said there was not much in terms of published data but suggested a round of lice shampoo the night before surgery.

“After careful prepping and draping, a louse was observed on the sterile field near the planned pin insertion site,” the article read. “The case was immediately canceled and delayed indefinitely.” I guess even orthopedic surgeons have their limits.

The authors speculated that dousing the hair with pesticide caused the lice to jump ship, hence the rogue louse crawling around the surgical site. Or maybe it was a coincidence. It was just one louse, after all.

But one louse is enough to ruin anyone’s day.

*****

Head lice affect up to 12 million Americans every year, costing close to a billion dollars. This price won’t be going down anytime soon, thanks to genetic mutations that help lice dodge the effects of the cheap, safe treatments that once worked so well.

Head lice, which are about the size and shape of a sesame seed, suck human blood but are not known to transmit any diseases. Image credit: Watercolor and ink by Veronica Tremblay for The Science Writer

Familiar household brands of lice shampoo like Rid and Nix contain pyrethroids, natural and synthetic forms of a chemical produced by the humble chrysanthemum, to ward off pests. Don’t let the “natural” designation fool you; it is a potent neurotoxin. Like its banned cousin, dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT), it kills by paralyzing the respiratory system. Fortunately, it leaves mammals unscathed, which makes it safe to slather on our heads. Unfortunately, decades of overenthusiastic pesticide use in agricultural and medical settings have given lice plenty of opportunities to adapt. In the U.S., at least half of head lice carry a genetic mutation that makes them immune to pyrethroids. So-called “super lice” aren’t so super these days.

Newer treatments are more effective, but many aren’t covered by health insurance, and some are only available by prescription. Topical ivermectin lotion, best known by the brand name Sklice, was approved for over-the-counter use in 2020 but is notoriously expensive and difficult to find.

Treatment trends are shifting toward non-pesticide options, like dimethicone, that smother lice by physically clogging their respiratory systems. Dimethicone is now used first-line in most of Europe and is becoming increasingly popular in the U.S. These products are often hyped as “resistance proof” because of their mechanism of action. But let’s not get cocky. Lice have evolved to withstand everything we’ve thrown at them; consumers and clinicians are already reporting that these products don’t seem to work as they used to.

Professional nitpickers are rising to the challenge. Specialized “lice clinics” that offer a chemical-free, spa-like delousing experience are an emerging industry. One popular chain, LiceDoctors, advertises some of the lowest rates: an average cost of $480 for a family of four. Many parents are happy to pay, and anyone who has gone a few rounds against lice gets why: They are tenacious little bastards. Thanks, evolution.

******

As I write this, I am idly scratching the nape of my neck. My sharp-eyed husband has checked and rechecked my hair a half dozen times in the past few days and reassured me I’m all clear. But I may treat myself with a round of pediculicide, just in case. I have a few bottles of Nix crème rinse stashed in my medicine cabinet. It may only have a 50-50 chance of working, but it leaves my habitually neglected hair feeling silky and pampered. Self-care is important.

But you can’t do it alone. Ask any troop of primates: Delousing is a team sport.

“Just hold the light for me. I really don’t mind doing this part,” my husband confessed during our most recent family nitpicking session. He seemed to enjoy himself, making the kids laugh with his impression of a chimpanzee patriarch: hooting, grunting, pretending to eat the nits he had picked out of their hair with his long, nimble fingers.

Lice may be inevitable, but it is important to keep them in perspective. After all, as my 10-year-old reminded her little brother, “Relax. It’s just itchy. It’s not like they’ll drain you of all your blood.”

Sarah Hartnett

Sarah Hartnett is a general pediatrician. She lives in Maryland with her husband, six kids, two dogs, and two lizards. Her family is parasite-free. For now.

Senior Editor: Lindsey Leake

Art Editor: Veronica Tremblay

Copy Editor: Sarah Donahue