Killing Her Softly

Mysterious cases of lung cancer are afflicting nonsmoking women; Congress must pass legislation now to investigate why

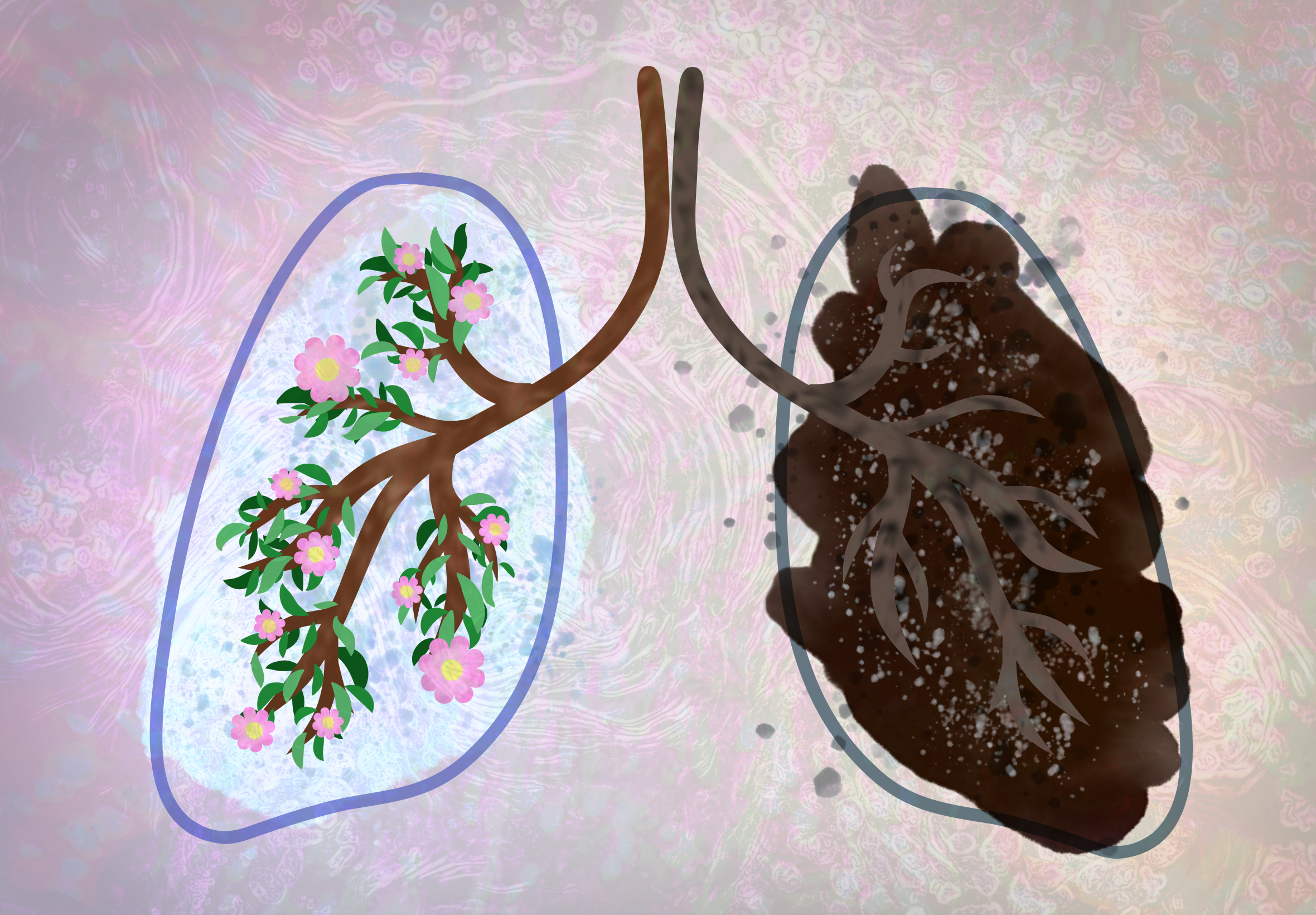

Credit: Rachel Lense for The Science Writer

Opinion

by Kara West

November 10, 2024

In the case of Rachel Smith, it started with a little cough. It was flu season, so Rachel didn’t think much about it. She was 31 years old, a strong, busy mother of two who worked full time as a flight nurse. Rachel and her husband, Todd, also a nurse, saw patients with far worse symptoms on a daily basis.

But winter turned to spring, and Rachel couldn’t shake the persistent cough. She also noticed her resting heart rate rising sharply. Despite multiple visits to the hospital, the true cause of Rachel’s deteriorating condition remained elusive. In desperation, the Smiths reached out to family friend James Pearl, a pulmonologist. When Pearl looked at Rachel’s CT scan, he was filled with dread. A biopsy confirmed the worst: the likely tumor he saw on the scan was non-small cell lung cancer. Rachel had never smoked a day in her life.

A selfie of Rachel Smith from a hospital bed. Credit: Rachel Smith

Six months after her lung cancer diagnosis, Rachel died.

Alarmingly, Rachel’s story is not an isolated incident or, it turns out, even rare. In 2023, more than 20,000 never-smokers in the United States died of lung cancer, according to a January 2024 report in Nature, and some studies suggest incidence of lung cancer in never-smokers is on the rise. Furthermore, lung cancer in never-smokers disproportionately affects women, who comprise about two-thirds of cases. In other words, women who have never smoked are two times more likely to develop lung cancer than men who have never smoked.

Historically, lung cancer rates in women were lower than in men, but that is changing for the younger generation. A study published in JAMA Oncology last October found that women between the ages of 35 and 54 were diagnosed with lung cancer at a higher rate than men in the same age group, even though women smoke at a lower rate than men. Although risk factors for sex differences in lung cancer risk might include genetics or environmental factors, current research is unable to sufficiently explain sex-based differences in lung cancer risk.

To investigate, the U.S. Congress introduced the bipartisan Women and Lung Cancer Research and Preventative Services Act of 2023. This legislation allocates funding for research to solve this medical mystery and reduce lung cancer mortality in women. Congress has introduced this bill in every session since 2015, and in every session, the bill has died in committee. It’s a bipartisan, noncontroversial issue. So, what is standing in the way?

Shame, it turns out, is one of the biggest obstacles to passing the bill, according to Laurie Ambrose, lung cancer advocate and key author of the legislation. Because smoking is a risk factor for lung cancer, the public widely perceives the disease as self-inflicted, and lung cancer patients frequently report experiencing negative social attitudes, according to a report in Oncology Nursing Forum. The study suggests that aspects of lung cancer stigma limit patient involvement in advocacy.

Addressing the pervasive stigma surrounding lung cancer, which has been linked to resource challenges, psychosocial distress, and poor patient outcomes, is a priority for advocacy groups, including the American Lung Association.

Ambrose, CEO of GO2 for Lung Cancer, said there is no entrenched opposition to the Women and Lung Cancer Research bill. Instead, the problem is overcoming stigma. “What moves policy is advocacy. What moves advocacy is numbers,” said Ambrose.

Yet stigma prevents more victims from speaking out; stigma stands in the way of forming a coalition loud enough to demand passage.

“The fact that there is an increasing number of never-smokers, particularly women, is the siren call to say, please, we cannot overlook this 800-pound gorilla that people don’t want to talk about because of the stigma that has been attached,” said Ambrose regarding lung cancer victims.

Breast cancer used to carry a similar stigma, yet as advocates spoke out and battled the stigma, funding, research, and prevention increased. Since 1992, which correlates with the advent of pink ribbons in popular culture, five-year survival rates for breast cancer have doubled.

Lung cancer is the deadliest cancer, killing more people annually than breast, prostate, and colon cancer combined. Yet relative to its lethality, lung cancer is underfunded. According to a study published in January by JCO Oncology Practice, from 2015 to 2018, breast cancer received over twice as much funding as lung cancer (from a combination of the National Cancer Institute and nonprofit organizations), even though lung cancer is about three times more deadly, based on median annual mortality.

It’s “the under-funded, under-recognized killer,” said Julie Luckart, a friend of the Smiths and a nurse practitioner who worked at Huntsman Cancer Institute for 12 years in thoracic oncology. Because it’s so difficult to detect at early stages, lung cancer is also a silent killer. By the time symptoms appear, the disease has often progressed beyond hope. The five-year survival rate is only 18.6 percent for lung cancer, and 48 percent of women diagnosed with lung cancer will not survive past one year. With so few lung cancer survivors, the pool of potential advocates to promote funding and research is greatly diminished.

It’s “the forgotten cancer — the invisible ribbon,” said Luckart, referencing the ribbons worn to draw attention to health causes.

Rachel represents the pain of just one family. The American Cancer Society estimates that nearly 60,000 women will die of lung cancer in 2024.

A RAND Corporation report commissioned by Women’s Health Access Matters found that by allocating just $40 million to lung cancer research in women, even modest returns would result in 22,700 years of life added, 2,500 years restored to the workforce valued at $45 million in labor productivity, and a 1,200% return on the investment.

“The funding is a drop in the bucket for them. Just give up one F-16. You’re good,” said Joseph O’Driscoll, Rachel’s older brother.

On February 14, the House Subcommittee on Health held a hearing on the Women and Lung Cancer bill. In that hearing, Rep. Anna Eshoo (D-California) provided some insight on why certain needs are addressed by Congress while others are ignored.

“Before I came to Congress, I thought that Congress was a proactive institution,” said Eshoo. “But I got here and quickly realized it’s a reactive institution — it reacts to the voices of people from across the country.” GO2 for Lung Cancer makes it simple for citizens to lobby congressional leadership in support of the Women and Lung Cancer Research and Preventative Services Act of 2023 on their website.

Passing the Women and Lung Cancer Research and Preventative Services Act is an important first step to uncovering the reasons behind the disparities between men and women with respect to this lethal disease. But it’s not just about preventing the senseless deaths of healthy young women. Investing in women’s health benefits all of us. Rachel was a flight nurse; the loss of her specialized talents and the lives she could have saved will have a huge impact on society.

Regarding her friend, Luckart said, “So much life has been lost. There’s no reason she shouldn’t be raising those babies. It’s almost impossible to measure the pain.”

Kara West

Kara West is a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University, studying science writing. She writes about sustainable food systems, renewable energy, environmental issues, and public health. Her four children and her husband, Taylor, are the loves of her life. She lives in the spectacular Wasatch Back mountains of Heber City, Utah.

Editorial note: The opinions presented above are solely the views of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of The Science Writer.

Senior Editor: Kristen Hines

Art Editor: Rachel Lense & & Kieran Tuan

Copy Editor: Sarah Donahue