Rapture at 31 Bars

A submersible pilot’s view from the deep reaches of the ocean

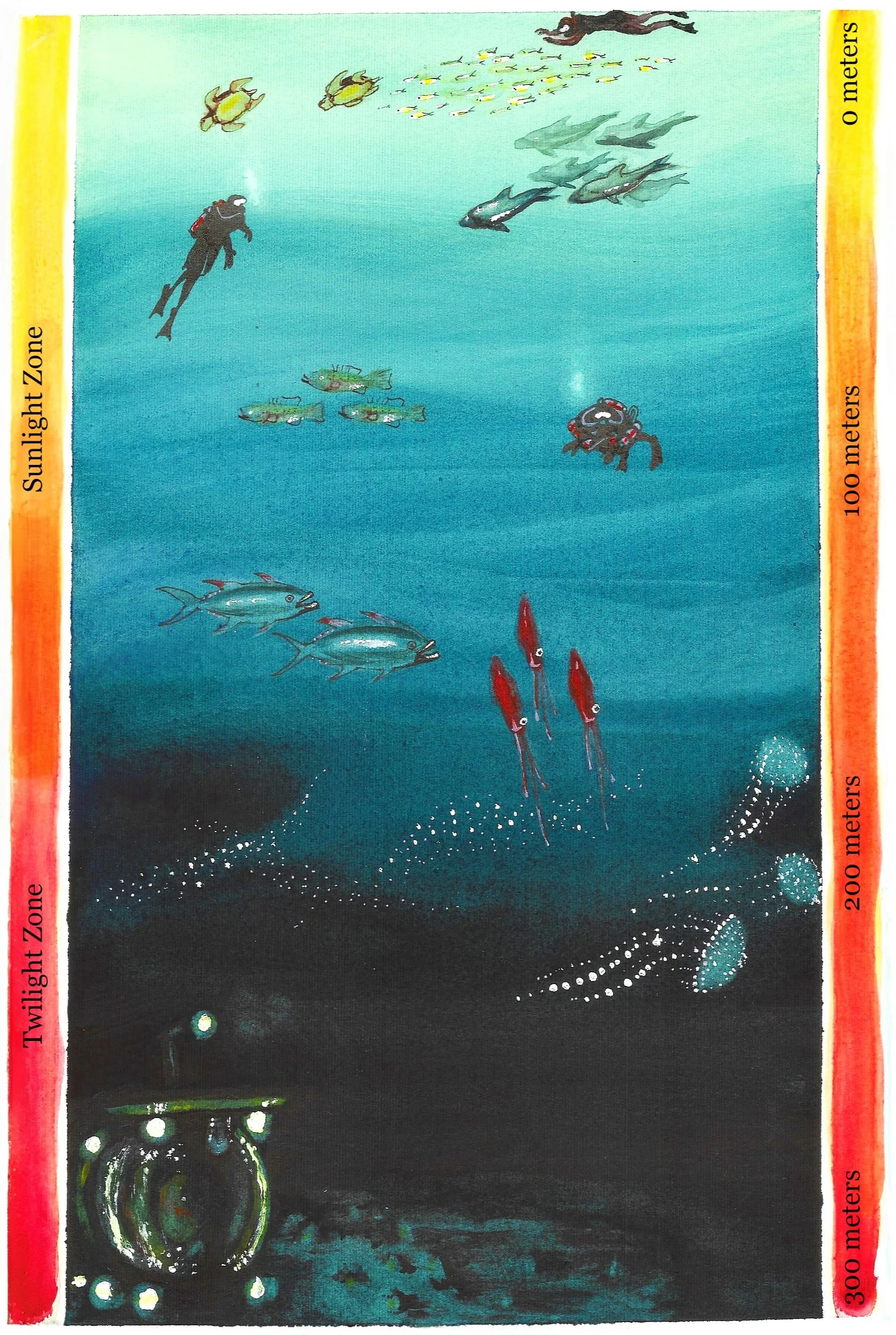

A watercolor rendering of a submersible in the darkened depths of the Mediterranean, approximately 300 meters down, surveying the sea floor. Image credit: Veronica Tremblay for The Science Writer

by Kara Weller

January 30, 2024

Topside, this is 71-3. My hatch is closed, locked, and secured; my equalizing valve is closed; my oxygen is on and flowing; my CO2 scrubber is running; my air con is on; and both air monitors are on. I am ready to set the timer on your mark.

71-3, this is Topside. Setting timer in three, two, one. Set.

Timer is set. Are you ready for my readings?

I give Topside readings of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and pressure inside the submersible; buoyancy; location details; battery status; as well as oxygen and high-pressure air levels inside the various tanks. Then, I shift my gaze from the main screen to the periscope camera and check the depth below me before calling again and getting permission to vent my tanks.

Venting tanks and going down for underwater comms check at 10 meters.

Calm comes over me. This is the part I like, when all preparations are complete. Nothing remains but to dive. I open the vent valves on the diving tanks, releasing air that lowers the sub in the water, so no part of its two acrylic spheres remains above. I turn my vertical propellers to full power. If my payload calculations are correct, I will have enough weight in the sub to descend.

At 10 meters, I call Topside and confirm our underwater communication system works. Then, I continue into the deep. One of the instructors is riding in the bow sphere, and a fellow pilot is in the stern. The sub can seat six passengers plus the pilot, but today we dive with just the three of us. They gaze out into the water through the domes as I scan the three display screens and air monitors in front of me.

We are diving off the east coast of Sicily, hiding from a storm raging around Malta; 40-knot winds and 3-meter waves prevent us from diving where we had originally intended. We are here as part of a search-and-rescue training with seven pilots, two subs, and two instructors. Nobody, instructors included, has dived in this spot before.

Little light reaches depths of 300 meters and pressures around 30 bars (435 psi). These extremes require plant and animal life on the sea floor to adapt in fascinating ways. Image credit: Veronica Tremblay for The Science Writer

The water is around 300 meters deep here (the length of six Olympic-sized swimming pools or three football fields). Excellent. A depth-protection system prevents our subs from going deeper than 300 meters, and we pilots and passengers find great satisfaction in reaching the bottom. Everyone likes to see what the seabed looks like. To me, our land-mammal selves are obsessed with topography, and seeing the ocean floor fascinates us more than whatever we find in the water column.

Seventy-one percent of the Earth’s surface is covered by water. That is why my sub is named 71-3; it is the third of our four subs. Deep oceans — below 200 meters, where sunlight has faded and darkness rules — are Earth’s largest habitats, yet we know little about them. Still, they hold insight into the global ecosystem and its life support. Every second breath we humans take comes not from rainforests but from phytoplankton, as oceans produce 50% of the oxygen on Earth.

Our surroundings appear devoid of life as we descend. Our vertical motion is barely perceptible to us, with no references outside with which to gauge our speed — only numbers on the screen steadily ticking away. But slowly, light from the surface fades. My red shirt turns purple, then black. Darkness envelops us.

Light is generally associated with life, warmth, positive energy, and happiness — darkness with the opposite. Many people fear the dark, and exploring the ocean depths in a confined space is not for everyone. Our dive is mere weeks after the Titan submersible tragedy, in which five people en route to the wreckage of the Titanic died from an implosion that left behind debris nearly 4,000 meters deep. But I am not worried about our safety — even as the pressure on the outer hull increases.

The vessel, with its acrylic spheres, has been checked and tested, and I believe it is safe. Although the weight of the ocean can crush and kill, there is a peacefulness inside these machines. Surrounded by dark water, there is no sensory deprivation, with screen lights blinking, propellers turning, our bare feet stinking, and fish flashing past the domes outside. But the bustle of life on land is far away. Phones don’t work here. Nobody can shout at us. We maintain communication every 15 minutes with Topside, which monitors our progress and life support, but otherwise, there is only us, the machine we drive, and the dark world with unknown life lurking in the depths.

The external pressure reaches 20 bars (290 psi) at 190 meters, then 30 at 290 meters. Two bars can inflate a car tire. Nine bars make a good espresso. Because pressure increases with depth, it is hardly surprising that when scientists pull deep-sea creatures out onto land, they no longer resemble their true selves. Humans have only rarely encountered such beings living in their own habitat. Adapted to such underwater pressure, these creatures morph into monsters when brought into our atmosphere.

The water swirls almost imperceptibly around us as we continue our descent.

Nearing 300 meters, I switch on my lights, illuminating the sea floor. A school of long, thin fish swarms around our domes, inquisitive eyes watching. While the fish resemble elegant silver pencils, the 9-centimeter-thick acrylic makes outside creatures appear smaller than they really are. The fish emit glints of light. In their presence, I feel at once small, reverent, and intrusive.

I switch off my lights. And then I lose myself, forget where I am. I don’t know if the others shriek with delight or become silent with awe, as I am no longer aware of them. I don’t know what I do with my arms and legs; I suspect they remain hunched in the awkward position a sub pilot must endure. I don’t know how long the feeling lasts, but for a moment, I believe I am standing outside in a meadow, looking up at a sky filled with brilliant stars.

Mentally, I travel in a flash from a depth of 300 meters to the light of outer space. Time is suspended, and my world becomes infinitely bigger.

The Mediterranean Sea has lost a vast diversity of species, and invasive species have added destruction to that caused by humans: overfishing and pollution. Perhaps I should be more curious about those creatures. But at the moment, I don’t think about any of this, as the beauty of bioluminescence consumes me.

“The language of light is much more prevalent in nature than most of us realize.”

Most deep-sea ocean animals produce light. Scientists believe bioluminescence evolved independently in the world’s oceans at least 27 times. Species use it to hunt prey, attract mates, confuse attackers, and give warnings. When threatened, some creatures shine their lights to attract even bigger predators that will then, hopefully, consume their attackers. The language of light is much more prevalent in nature than most of us realize. And although I have seen bioluminescence at night from the surface of the water, never have I been immersed in it.

I am hardly aware of the rest of the dive. I know I continue and, almost an hour later, inform Topside I am bringing 71-3 back to the surface.

At 10 meters, I ask Topside for permission to blow my tanks, then release high-pressure air into my dive tanks to shoot the last few meters to the surface. I raise my freeboard extender, switch my sonar screen to display the periscope camera view, and equalize the pressure in the sub.

Unlike scuba divers who undergo pressure changes as they dive, the enclosed system of the sub maintains a mostly steady pressure throughout, regardless of depth. If I add more water to the buoyancy tanks, pressure may increase inside. If it gets too hot, pressure can rise. If I use too much air conditioning, pressure may drop. Small adjustments must be made via the sub’s equalizing system at the surface before the hatch can be opened.

I open the hatch, and the glaring heat of the midday Mediterranean sun blasts my skin. The people who beetle about onshore are unaware of the delight that lies so near, below the depths of their city. I pity them.

***

Months later, I sit at my desk in the cold of a Finnish winter, daylight fading as stars begin to illuminate the sky. I once gazed at them with thoughts of distant worlds and galaxies yet to be explored; now they recall the wonders I witnessed here in our ocean on Earth and how little we still know about our sparkling planet.

Fish lights dance in the sky.

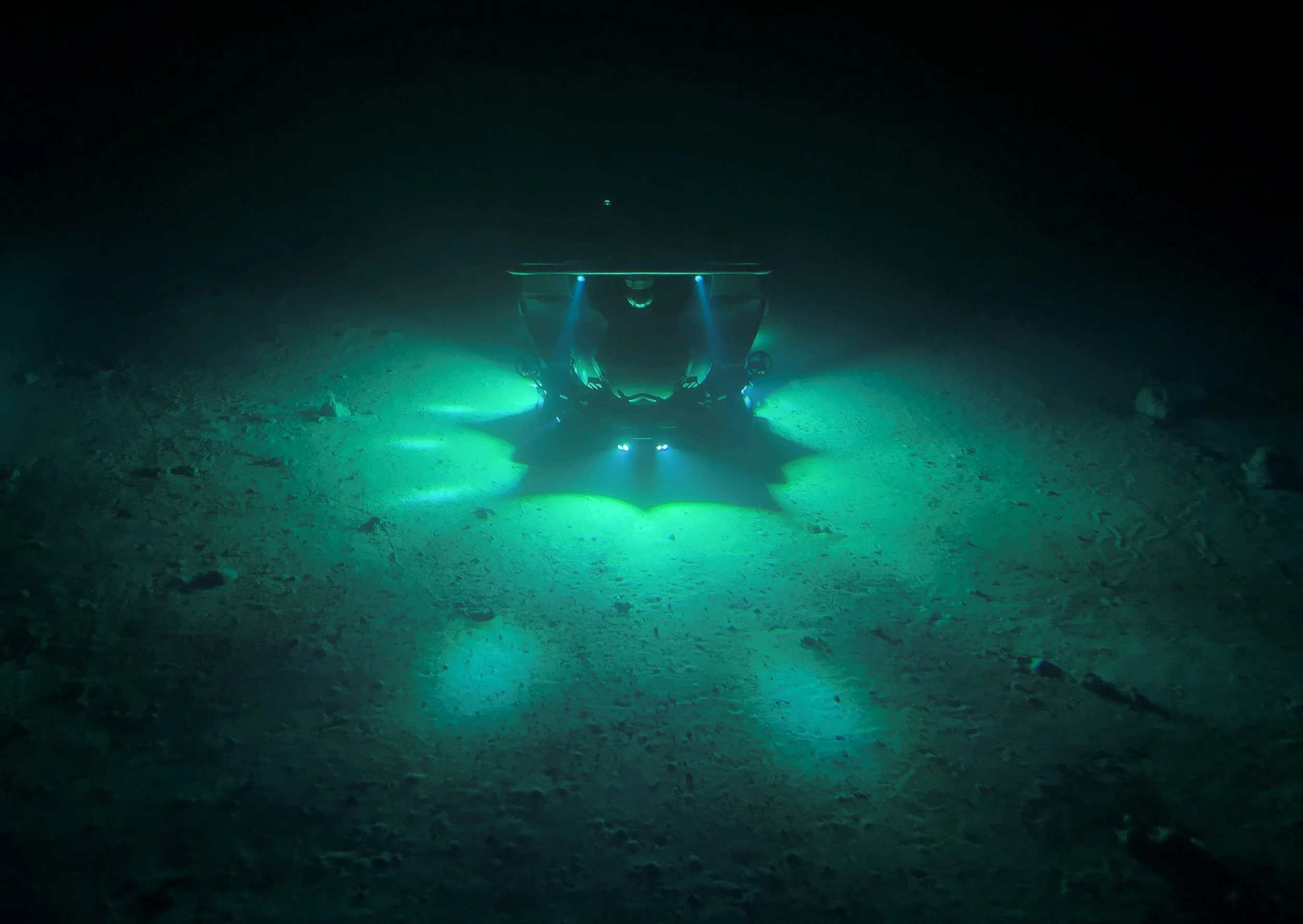

One of the submersibles Kara Weller’s organization uses to explore the Mediterranean Sea at 300 meters below sea level. Image credit: Kieran Buckley

Kara Weller

Kara Weller started a career in wildlife biology before shifting to international adventure tourism. A naturalist for more than 25 years, she has worked on over 200 trips to Antarctica, visited the geographic North Pole six times, voyaged up the Amazon River, explored caves in the Faroe Islands, and been overcome by heat stroke in West Africa, among other adventures. She became a qualified submersible pilot in 2022 and continues her adventures underwater.

Senior Editor: Lindsey Leake

Art Editors: Rachel Lense & Veronica Tremblay

Copy Editor: Christopher Graber