The Sleuths Searching for Montana’s Lost Apples

Heritage apple hunters scour the past to plant the seeds of food resilience

Illustration from “Productive Orcharding, Modern Methods of Growing and Marketing Fruit” by Fred C. Sears published by J.B. Lippincott company, c.1917. via the Library of Congress.

By Annabelle Moore

December 6, 2022

A glossy apple with ombre shades of red, orange, and green bobs gently on its branch in a dry Montana breeze. This isn’t an ordinary apple. It is an heirloom. A gift from prior generations of Montana farmers to those living in the region today. A gift that may help secure a more resilient local food system — that is, if apple detectives can capture and preserve its genetic secrets before its gnarled, elderly tree dies.

Bitterroot Valley, Montana. Image credit: SheldonPhotography, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

Clustered behind an A-frame log cabin on the northwest shore of Flathead Lake lives the heritage orchard of Tobi and Patrick Campanella, home to this extraordinary apple. For more than three generations, Tobi Campanella’s family has cared for 125 trees first planted around 1898. Made up of Lodi, Duchess of Oldenburg, and Wealthy varieties, among others, the Campanellas’ legacy trees are over 75 years old — the minimum age to be considered a heritage apple.

“We’ve got apples that most people have never heard of,” says Tobi Campanella. Learning to care for their heritage trees has become an unexpected adventure in flavors for the retired university administrator. She describes some of her apples as “fruity,” like “bananas — not in texture, but in taste.” And just as her mother showed her, she crafts their fruit into juice, sauces, dried fruits, jams, and a “killer” pie.

“I’ve used the apples for the local kids’ lunch programs,” she says. “The kids are always interested. I was surprised they noticed it wasn’t a store-bought apple.”

The Campanella orchard is one of over 70 cataloged in Montana State University’s Montana Heritage Orchard Program, also known as MHOP. For the 58,000 Montanans who live over 10 miles from the nearest grocery store in so-called food deserts, accessible fresh fruit is stocked far out of reach.

MHOP was founded in 2013 by researchers Brent Sarchet and Toby Day, who saw an opportunity to use Montana’s rich fruit-growing history to nourish current and future residents. The program’s goal was twofold: first, to rediscover, document, and share the story of Montana’s heritage trees; and second, to preserve the genetic diversity and resilience of heritage apples that thrive in the state’s harsh and variable climate. Funded by a U.S. Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Block Grant, the program helps landowners like the Campanellas identify lost apples and document their orchards’ histories, and it offers guidance for care and propagation. MHOP’s researchers hope the apples, used privately or commercially at farmers’ markets and cideries, will boost agritourism in rural economies. The heritage apples MHOP tracks are rooted in Montana’s homestead history.

The cover image from a 1909 promotional pamphlet produced by the Bitter Root Valley Irrigation Company “The Famous McIntosh Red of the Bitter Root Valley: An Opportunity for the Nonresident Investor and the Prospective Resident." Image credit: Archives & Special Collections, Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library, University of Montana.

In the mid-1800s, either unaware of or uninterested in the native ecology, homesteaders and gold seekers sought a familiar source of sustenance and planted fruit orchards upon moving to Montana. During this time, one valley named the Bitterroot may have boasted 10,000-15,000 acres of apples. But changing agricultural practices and farm boundaries have left many of these orchards abandoned. Luckily, heritage trees are hardy. They’ve survived decades of neglect, drought, disease, pests, and harsh winters — and they still produce apples. And there is a genetic resilience in these apple trees that is worth saving.

Worldwide, humans grow some 7,500 genetically distinct apple varieties. Commercially, though, less than 20 types dominate U.S. grocery stores, including Red Delicious, Granny Smith, Fuji, and Gala.

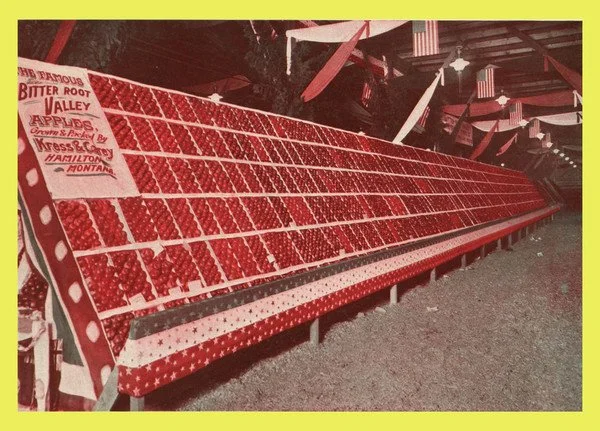

McIntosh Apples harvested from Charlos Heights Orchards, Bitter Root Valley, 1909 featured in the promotional pamphlet Bitter Root Valley Irrigation Company. Image credit: Archives & Special Collections, Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library, University of Montana.

“One thing people don’t understand about apples is there is so much diversity [in their] purposes and uses,” says former MHOP program manager and apple enthusiast Katrina Mendrey. “The seasonality of [apples] has been lost in how we eat as a modern society.” Some apples were developed to be scrumptious raw. Others are best used to make sauces, hard ciders, baked goods, vinegar, or to set jams. Through education and outreach, MHOP encourages growers to sustain or plant these resilient trees to strengthen local food systems and increase public access to healthy produce.

Crop diversity isn’t just about having more kinds of apples to choose from in the local grocery store; it’s about creating a secure food system. Relying entirely on just a few types of apple trees, and thus reducing the beneficial genetic mix of attributes, increases the likelihood that an entire crop will collapse if exposed to a fell swoop of pests, disease, and climate change-induced weather extremes. Our food systems are strengthened when farmers and growers plant a variety of trees with a multitude of defensive attributes that can thrive and produce fruit reliably within the local environment.

To this end, several universities and citizen science groups are working together across the country to trace lost apples through historical agricultural records and genetic tests. John Bunker, who has been an apple sleuth for 40 years, echoes the sentiment of apples as “a gift from the past.” At a recent Heritage Orchard Conference hosted by the University of Idaho, Bunker explained that the years after the Civil War saw the last major planting of diverse apple trees. “Those trees are now approaching 150 years old,” he said. “We’re facing the inevitable death of many varieties we have yet to rediscover. It’s important to get out there and find them now.”

Once trees are found, there are practical and financial hurdles to overcome. Besides the cost and labor needed to care for the trees, there is also the cost of genetic identification, which relies on limited academic funding. An apple’s genetic history unfolds by extracting its leaf DNA, which encapsulates the genetic instructions passed down from mother and father. Every apple seedling has a unique mix of genetic qualities from each parent. “It’s like having children; they’re different from us in some really big ways,” Mendrey says. The quest is then to discover the identities of the parent trees, which will give an idea of the attributes the offspring may have. “If there’s a tree that [can] produce food in eastern Montana, that has a lot of food insecurity, and we lose that genetic makeup of that tree, then it’s lost forever,” says Mendrey. “Is it the only one left? Who knows?”

There are several methods to isolate DNA, from simple to complex. Which method scientists use depends on what questions they have about the apple. This in turn determines the amount and quality of DNA required for the study. Apple DNA is packed in storage units of 17 corresponding chromosome pairs. Scientists untangle and analyze the apple DNA in the form of single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs (pronounced “snips”), specific sections of genetic code along each strand. Thousands of SNPs, containing thousands of patterns, are a powerful comparison tool, like a fingerprint. Scientists line up the snippets of code in computer spreadsheets against other known apple genetic profiles. When two apples have multiple SNP sequences that match, an identity is found.

Worldwide, there are several apple databases with varying numbers of profiles. The most expansive in the U.S. is the USDA’s Plant Genetic Resources Unit in Geneva, New York. The unit functions as both a living and stored genetic archive of important plants in U.S. agriculture. Its significant collection of diverse apples features 6,079 samples of modern and heritage varieties.

If the apple isn’t in the database or is a unique seedling, there won’t be an exact match. But this doesn’t mean the case goes cold. Each analyzed apple expands the genetic library, which provides USDA scientists and other researchers around the world with increased data to conduct projects on common diseases, pest tolerance, and new management techniques. Genetic analysis used in combination with historical agricultural records helps apple enthusiasts sort out hidden apple identities that have been lost or mislabeled in the thousands of common names known in North America.

The biggest challenge in preserving old trees is caring enough to do it. After years of neglect, they’re often in rough shape. Moth-eaten fruit and unwieldy branches make trees tricky to prune and spray. “Unless the owner sees value in that tree, either historically, emotionally, or agriculturally, then often they’ll get chopped down, because they’re a nuisance or in danger of falling apart,” says Mendrey.

The Old Apple Tree of Vancouver, Washington c.2016. Photo courtesy of City of Vancouver, Washington, Parks & Recreation Department.

In the summer of 2020, the “Old Apple Tree” of Vancouver, Washington, died at 194 years old. To capture the qualities of a desired tree, like this cherished seedling, growers take a wood clipping called a scion and graft it to a rootstock, the trunk and root system of a different apple tree. The scion wood produces a freshly cloned tree. Thanks to grafting, future generations will enjoy identical green apples from Washington’s tree.

That same summer in Montana, Mendrey and her colleague Zach Miller, an associate professor of horticulture at Montana State University, discovered an unusual hybrid apple tree — a seedling blend of the McIntosh and Wealthy varieties — thriving on the side of a road. It was fortuitous that the “consistent large crops of delicious, early fall apples” drew their notice, says Miller, who collected several scion wood clippings. Later that year, to clear space for a building project, the tree was demolished.

Their hunt is paying off. In collaboration with Cameron Peace, a fruit geneticist at Washington State University, MHOP has genetically identified a couple of rare apples, including the McMahon and Early Red Bird (also known as Crimson Beauty) varieties. The team has also discovered exceptional seedling hybrids from lost heirloom parent trees, which “should be well adapted to grow in Montana, surviving a century or more,” says Miller.

The researchers will continue to work on an ongoing study to learn which rootstocks are best suited to tolerate pests, disease, and cold temperatures in the state’s short growing season. Like the Washington tree, scion wood collected from heritage trees is grafted onto test rootstocks to create new apple trees. In 2019, according to Miller and Mendrey, MHOP sold 179 trees to public nurseries across the state.

The autumn of 2020 brought a bitter Arctic cold front that damaged the fledgling trees with life-threatening low temperatures. In nearby Potomac, Montana, the temperature plummeted to minus 29.2 degrees Fahrenheit. Two hundred and ten preserved heritage trees survived the severe weather. Some of these will blossom and become available to the public in spring 2023.

Hidden in plain sight along rural roads, wild waterways, and irrigation channels, the latest batch of heritage trees added to the program’s catalog come from three apple seedling varieties: Summerdale, Luella Moon, and Moon-Randolph. Montanans interested in starting or rejuvenating an orchard can choose from 10 varieties of heritage trees genetically identical to those planted decades ago. The apples grown in the future will have flavors just as sweet, crisp, sharp, and tangy as their predecessors.

For the Campanella family, the steep learning curve and hours spent observing insects, soil, weather, and water conditions have paid off. “There are a few reasons people do this — one, for the nostalgia and legacy of having an orchard from your great-grandparents,” Patrick Campanella says. “Next is the monetary value in selling apples to promote your hobby and passion, and there are tax advantages for people who have the right parameters for agricultural status. [Orchards] help some people maintain their old family farms.” The Campanellas plan to have next year’s harvest genetically tested.

Back at MHOP, researchers’ desks continue to overflow with anonymous apples sent by fruit detectives. “It's good to keep these trees going, because eventually, they [will] die,” says Mendrey. “And hopefully, we’ll have new ones to take their place.”

Annabelle Moore

With dirt up to her elbows foraging for wild vegetables in Japan, Annabelle Moore realized she wanted to tell stories about people and nature. She is a student in the Johns Hopkins University Science Writing Program and enjoys writing about anthropology and ecology.