Marginal Dreams

A B-cell journey (abridged)

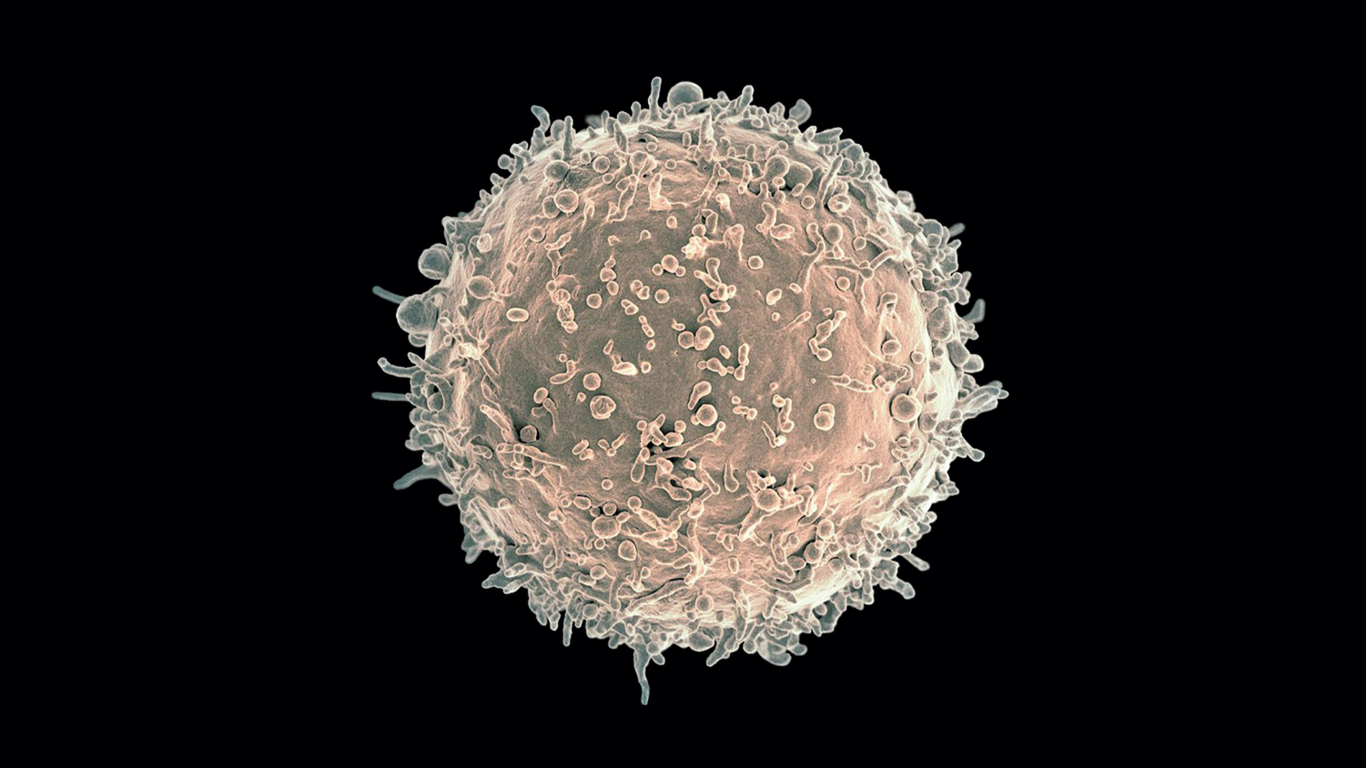

A human B cell captured through scanning electron microscopy. Image credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

by Myo Oo

June 10, 2022

I had a dream I was a marginal-zone B cell. In my dream, I live in the marginal zone of the spleen, a macho organ, home of the armed forces, known for its defenses against myriad infectious agents. Juxtaposed between the red and the white pulp of the marginal zone in the spleen, I gauge and guard against any incoming pathogenic insult. I am what you would call a frontline soldier, one that does the heavy lifting for the rest of the troop. My purpose in life is to serve in this vicinity. Strategically positioned and securely fastened in the marginal zone, I sieve through the blood to pick out any blood-borne pathogens, acting as surveillance. Born in the bone marrow, I have changed many lives, changing from a pre-pro-B cell to a pro-B cell to a pre-B cell to an immature B cell to a transitional B cell to my current life as a marginal-zone B cell. I have lived in different residences across my many lives, moving from the bone marrow to other lymphoid organs before calling the marginal zone my final home.

In my new home, there are thousands of my doppelgangers. I prefer to call them my twin brothers and sisters instead of clones. Although for the most part we are the same, we are also different. At times, my siblings and I express ourselves with subtle differences, showcasing our not-so-apparent individuality. For one, each of us excretes varying degrees of cytokines, instructional molecules that direct other cells on how to behave when challenged by a pathogen. And while our cellular infrastructure is somewhat similar, we make different amounts of proteins known as neutralizing antibodies to destroy undesirable pathogens in this marginal area. And when displaying foreign particles to other cells, our presentation of these particles can range in strength. So you see, we are the same and still different.

As a marginal-zone B cell, I am a type of maxed-out B cell, one that has reached full maturity, has a photographic memory, and has the license to kill. To reach this potential and to reach my new home, I have followed the well-worn path of being thoroughly trained and intensively fine-tuned in a blockbuster action called somatic hypermutation. The bulk of this occurs in a region called the germinal center of the spleen, where I first encounter the pathogen in question. Almost always instantaneously, my cellular machinery is activated to produce more doppelgangers like myself. And with the interaction with neighboring T cells, a select group of my brothers and sisters and I are subsequently chosen. Here, some of our genes are switched out to produce highly potent and highly specific neutralizing antibodies that are lethal to the invader.

At this crossroads, some of my brothers and sisters commit and transform into plasma cells. They then specialize in producing copious amounts of specific antibodies against this pathogen. Others, like myself, choose a different path. We remember this pathogenic encounter. We do not forgive or forget. The next time we meet the same insult, we are ready to defend and destroy. We acquire memory status, earning the name “memory B cells,” a type of mature B cell. Once we’ve reached this status, we make our way back home to the marginal zone, awaiting and ready for the next insult.

“My fluidity, my plasticity, and my dynamism are the very reasons I am so difficult to study.”

In my dream, I have many sets of hands jutting out from my cellular membrane. Scientists, who like to call my hands proteins, define me by using a few sets of protein markers for easy recognition. They try to peg me as a marginal-zone B cell because I have CD1c, CD19, and CD20 markers on the outside of my membrane. My hands serve as landmarks. Nonetheless, I am fluid. I am plastic. I am noncommitted. My expression is dynamic. I can acquire other hands that could easily transform me into other types of B cells, allowing me to sneak out of the marginal zone area disguised as another. My fluidity, my plasticity, and my dynamism are also the very reasons I am so difficult to study. Current nomenclature in the literature fails to fully define or track me.

In the marginal zone, I thrive, I rule, I conquer. I am the all-powerful cell. From time to time, however, my victories transform into defeats. In some of my defeats, my cellular machineries are far from fail-safe and can break down in unimaginable ways. In one of those punishing defeats, I am born with an overactive nuclear factor-κB pathway, critical to making sure I produce the right amount of cytokines, multiply in the right amount, and live to and die at the right age. When born with this defect, my cellular apparatus goes awry. I go rogue, and I multiply at an unprecedented rate, enveloping the marginal zone with an arsenal of cancerous marginal-zone B cells like myself. Clinicians call this splenic marginal-zone B cell lymphoma, a type of rare non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Patients with this condition have reached the winter of their lives. This is when a slow death begins, and the terror starts.

In my marginal dreams, stories of my victories and my defeats are deeply intertwined. I am, after all, still a living being — highly evolved, yet still vulnerable to forces of nature. A few missing or extra enzymes can easily reduce my biological utility to zero. Just as they say, nothing is certain in life. But it is at least good to keep dreaming.

Myo Oo

Flow cytometrist Myo Oo spends much of her time studying the crosstalk between proteins and immune cells during tuberculosis infection. When she is not surrounded by one too many cytometers, Myo is busy advocating democracy for Burma. She is a graduate student in the Johns Hopkins University MA in Science Writing Program and lives in Nutley, New Jersey.