Suicide Crisis in the Irish Travelling Community

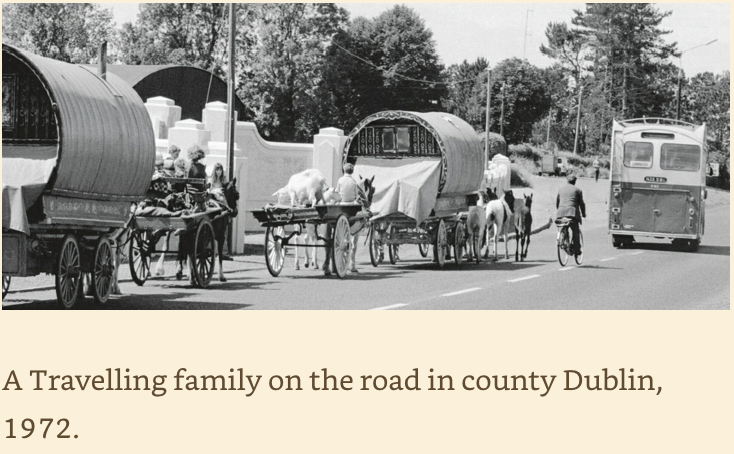

Photo retrieved from the book "Irish Travellers, The Unsettled Life" written by George and Sharon Gmelch. Published by Indiana University Press in 2014. (Photo credit: George Gmelch)

In 2000, suicides in the Irish Travelling community were three times the rate of the country’s general population. Today, suicide is six times the rate of the settled community. For Traveller men aged 15 to 25, it’s seven times as high.

As a small ethnic minority—estimated to be about 30,000—Travellers once roamed the country, working casual labor, moving on when jobs dried up or rows flared with local settled people. This peripatetic life put families under high levels of economic, social, and environmental stress. Although these stresses have been around for centuries, suicide was never a significant issue—until now. Experts are unsure what exactly is causing the current spike, but they do point to issues such as mental health stigma and laws that limit movement.

John O’Brien, who manages a Traveller-specific mental health and suicide prevention service in Dublin, believes that Travellers are “experiencing a loss of identity.” The 2002 Trespass Act made it an offense to enter and occupy land, meaning they no longer have the right to set up camp wherever they wish. Today, 95 percent are housed either in fixed accommodation or at official, often-crowded sites where their caravans are parked permanently.

“Now,” he says, “many don’t know what being a Traveller is anymore.”

O’Brien also feels that the current trend in Traveller suicide is being fueled by the “outpouring of love on social media” following a death. This results in an almost “glorification of suicide,” he says, which is contributing to the contagion effect.

Irish Travellers “remain one of the least assimilated of Europe’s itinerant groups,” according to anthropologists George and Sharon Gmelch. As a result, individual Traveller families are close-knit. Although a family with close bonds normally acts as a buffer against the risk of suicide, in this case strong relationships may be fueling the problem, especially amongst adolescents.

“Exposure to suicidal behaviors in significant others may teach individuals new ways to deal with emotional stress,” according to a 2014 study by Seth Abrutyn and Anna Mueller. These social ties can provide not only social support but can also contribute to anti-social behaviors, the authors found.

Photo retrieved from the book "Irish Travellers, The Unsettled Life" written by George and Sharon Gmelch. Published by Indiana University Press in 2014. (Photo credit: George Gmelch)

According to an earlier study by Gould, Wallenstein and Davidson, the occurrence of suicides in the community or in the media may produce a familiarity with and an acceptance of the idea of suicide. Taking one’s own life is seen as a learned choice of action, just like any other.

The government and institutional response has been muted. Irish mental health services do not record the ethnic status of their patients, making it hard to determine the exact numbers seeking treatment within the health system. Travellers that enter the system often end up declining the free services offered, says Dr. Fiona McNicholas, a professor of child and adolescent psychiatry working with CAMHS (Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services).

McNicholas attended one young Traveller patient admitted to the hospital emergency department for self-harm.

“When I tried to encourage the mother to enroll him for counselling, she refused, saying the problems her child was experiencing was a cross God had sent her to bear,” she says.

McNicholas feels there is a significant stigma attached to mental health within the Traveller community, and, until that changes, existing services will not be accessed in significant numbers.

Anthropologist Sharon Gmelch agrees. There is “a stigma associated with and discomfort talking about mental health issues,” as well as “an unfamiliarity with mainstream societal institutions.” There are “communication difficulties within the community, feelings of hopelessness, and an acceptance of suicide (especially if family members have already done it) and not seeing an alternative.”

O’Brien, who runs the Dublin mental health service, says the reluctance of parents to engage has a lot to do with the fear of their children being taken from them by social services. Many women believe if they talk about their depression, they will lose their child, says O’Brien. In the past Traveller children were removed from the community and placed in institutional care. Travellers had a name for the person who came to take the child away. “He was known as the cruelty man,” he says.

In 1971, Sharon and George Gmelch embedded themselves in the community for a year, returning in 2011 to see what had changed. Although heartened to see young Travellers now in school full time and some women working locally, they believe settled life has left many people, particularly men, feeling lost. Their book, Irish Travellers, The Unsettled Life reveals much about the challenges still facing the families they visited. In it, Jim Connors, a member of the community, talks about what happens when frustration with life boils over.

“One result,” he says, “is to damage yourself, damage your property, or damage something else.”

“Travellers are rather stoic,” the Gmelchs say, “which makes expressing feelings or doubts—anything that might be interpreted as weakness—difficult. When the vocabulary to label a phenomenon like “discrimination” does not exist, it is perceived as individual experience and kept private, and the pain it causes goes unabated.”