In Bid To Reduce Black Maternal Deaths, Virginia Eyes Doula Solution

Gov. Ralph Northam signed a ceremonial bill in June 2019 to eliminate the Black maternal mortality disparity by 2025. (Photo courtesy: The Office of the Governor of Virginia)

Plan to End Racial Disparity by 2025 Must Still Clear Hurdles Before, After Launch

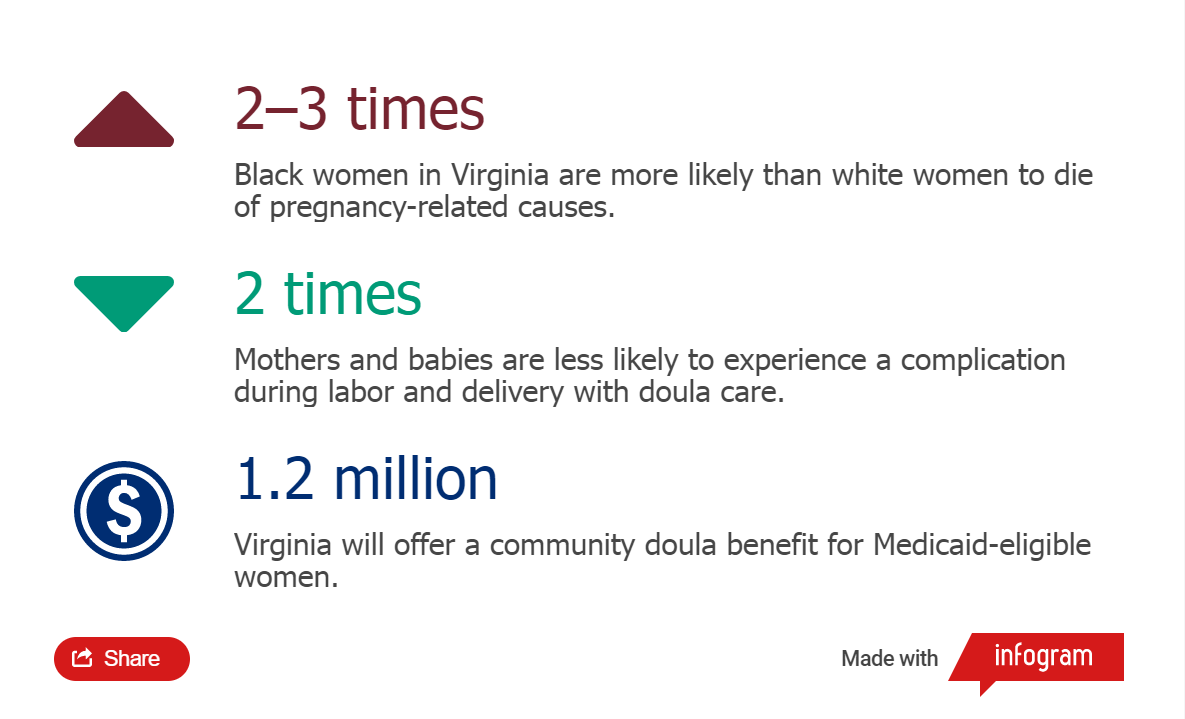

Virginia is poised to implement a new health care strategy that aims to eliminate a troubling racial disparity: Black women in the state are two to three times more likely to die of causes related to their pregnancies than white women. Starting in April, Medicaid-eligible women will be offered a community doula benefit.

Infographic by Kristen Hines

Doulas are women who work without formal obstetric training yet provide valuable guidance and support through pregnancy and recovery. The coverage, which includes eight case visits and attendance at the birth, is a key component of Governor Ralph Northam’s goal to end the disparity by 2025, while improving other pregnancy-related outcomes.

Northam, a pediatrician, has proposed an inaugural $1.2 million to establish funding for the doulas. About 30 percent of the 97,400 live births in 2019—21,293 of them being Black babies—were covered by Medicaid. The governor’s first-year investment appears predicated on a gradual embrace of services, which could end up reimbursing close to $1,000 per client if all benchmarks are met.

The doulas are part of the governor’s larger maternal health plan, which has already begun to address the mortality rate by expanding access to other Medicaid options. But community doulas rose as a leading solution to the racial disparity because the information they provide—on everything from prenatal nutrition to postpartum mental health—comes from individuals to whom mothers can relate culturally. Although they aren’t allowed to perform clinical tasks, doulas can help a woman formalize her birth plan and provide other forms of comfort and support.

Doreen Bonnet is co-founder and executive director of Birth Sisters of Charlottesville, Virginia. (Photo courtesy: Doreen Bonnet)

At least one study has shown that mothers are two times less likely to experience a birth complication for themselves or their babies when paired with a doula. Metrics such as birthweight improve as well.

Doreen Bonnet is co-founder and executive director of Birth Sisters of Charlottesville, a nonprofit group that matches women of color in the community with experienced doulas like herself. Bonnet looks to align race and cultural background as much as possible. She said she is optimistic about the governor’s plan, which has been informed by stakeholders across the state.

“Medicaid reimbursement for doula services would help us reach more mothers and support the sustainability of our organization,” Bonnet said.

Her clients frequently express frustration with their maternal health care in Charlottesville, she said. The Charlottesville area is served by two hospitals, the University of Virginia Medical Center and Martha Jefferson Hospital. The city is not unique, however. Similar stories of alienation have been reported throughout the state and nation.

“If you are a person of color growing up in this country, the number of stressors you are faced with has an impact on your body, your system, your capacity to have a healthy birth,” Bonnet said, referring to the “weathering” theory, which has gained acceptance as researchers have built knowledge about the cumulative effects of stress. “And obviously bias has an impact. Sometimes women of color are not taken seriously, or when they say they’re having a symptom, they’re not believed.”

Bonnet said she knew of only one Black OB-GYN in the Charlottesville area. That doctor is participating in a three-year academic fellowship at the University of Virginia that involves two years of clinical rotation. None of the local midwives, who are trained to provide clinical services and deliver babies, are Black to her knowledge. (A spokesperson for Martha Jefferson Hospital confirmed that it does not currently have any Black OB-GYNs or midwives on staff, while acknowledging the problem. Spokespersons for UVA Health System did not respond to questions.)

Dr. Vanessa Walker Harris, state deputy secretary of health and human resources. (Photo courtesy: Virginia Health and Human Resources)

While a care provider of a different race can still give excellent care, Bonnet said, discrimination isn’t always conscious and may not always come from the medical professional. A slight by anyone on staff could serve as a wedge that impacts health.

“It’s not just bedside manner,” she said. “It’s the overall culture they create on their teams.”

Although large dataset research is lacking on the value of having racial matching between doulas and their clients, case studies and anecdotal evidence suggest a positive connection. Existing research has demonstrated that racial similarity influences a patient's comfort with her provider, and that Black patients believe Black doctors better understand their health needs.

The main criticism of doulas has stemmed from reported conflicts between doulas and hospital staff, most often in the delivery room. Some doctors and nurses view them as obstacles to care if they step beyond the bounds of their training. But the state is taking the position that their benefits outweigh any problems that might arise.

Dr. Vanessa Walker Harris, state deputy secretary of health and human resources, said the community doulas will be Medicaid’s “eyes and ears” because they “get clients access to care and make sure they are heard.”

Currently, only a handful of states—Oregon, Minnesota, New York, and Indiana—offer a doula benefit. Virginia’s plan looked to be the most generous when first proposed. Now, New Jersey’s developing benefit tracks to be competitive, Harris said. Georgia is also working on an offering.

Lisa Brown, co-founder and deputy executive director of Birth Sisters. (Photo courtesy: Lisa Brown)

Lisa Brown, co-founder and deputy executive director of Birth Sisters, was appointed by the State Health Commissioner to the Virginia Doula Task Force. She joined along with a former client, Lora Henderson. They have been among those both providing and receiving input toward the goal of getting state regulations and certification guidelines in place. At present, with no legal requirements to practice in Virginia, it’s unclear exactly how many doulas currently work across the state and how many might pursue state certification.

Brown said she is concerned Medicaid’s rules won’t align with client-centered care that promotes self-determination. She and Bonnet still have a number of questions, which should be answered in the months ahead.

Bonnet, for example, said Birth Sisters is often called when a woman is in her final days of care or already in the hospital for labor and delivery. She is uncertain how Medicaid preapproval requirements will work then.

The doulas are bracing for a lot of paperwork, which they say is a necessary means to an end. While existing grants provide Birth Sisters’ Medicaid-eligible clients a free service, the addition of Medicaid reimbursement funds will help ensure that continues.

Northam announced his ambitious 2025 goal in 2019. But now with a spring start date, the program will have less than three years to achieve its objective. And since Northam’s term-limited service as governor ends in January, continuation of the fledgling program hinges on the backing of the next governor.

Why Black mothers are dying

Nationally, the Black maternal death ratio is about 2.5 times that of white women, according to the CDC, and experts believe Virginia’s maternal health mirrors that picture. The US leads the industrialized world in poor maternal outcomes, and Black women have always suffered disproportionately.

Research shows unaddressed chronic health conditions, such as high blood pressure, are the leading cause of death in Virginia and nationwide, exacerbated by a disconnect from health care providers. According to Virginia’s Maternal Health Strategic Plan, released in April:

“Black women were more likely to report chronic conditions like hypertension and depression and more likely to report experiencing discrimination or harassment due to their race/ethnicity or insurance or Medicaid status.”

Lack of care coordination, in particular, has been cited by Virginia’s Maternal Mortality Review Team—“with many women left to navigate the complicated healthcare system on their own.”

The second leading cause of death in Black women in Virginia during pregnancy is homicide.