Australian First Nations Remote Communities Lead the Way on COVID-19

When word of a new respiratory virus reached Dr. Lorraine Anderson, she was worried. Dr. Anderson—medical director of the Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Service (KAMS) in Broome, Western Australia—had worked during the H1N1 epidemic in 2009 and knew that First Nations people are at higher risk of severe infection because of problems such as chronic health conditions and poor housing. So she started working on a pandemic plan with her staff immediately.

“I was concerned we were going to lose all the old people and the culture and history they carry with them,” she said.

APY Border Closure. (Photo courtesy: APY- Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands, Facebook)

The Kimberley is one of the most sparsely populated areas on earth, with about 36,000 people living in an area roughly the size of California. The land stretches from red sandstone cliffs through rocky plains and gorges that flood during the tropical wet season. When the rains come, many smaller Aboriginal communities are isolated for months from the larger towns and health clinics.

In 2020, this remoteness turned from health care barrier to advantage. As of July 2021, official reports show only one case of COVID-19 in an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person acquired in a remote community. Nationwide, as of late August, one Aboriginal person (not in a remote community) had died from COVID-19.

Before the virus hit Australia, Richard King had been fearfully monitoring the situation in China. The general manager of the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands in the deserts of central Australia, King said he thought, “This is going to devastate us if we don't close our borders.” As the first cases of COVID-19 were detected in Australian cities, he moved quickly, imposing a lockdown of the communities on the APY Lands.

Australia has had low rates of COVID-19 because of geographical isolation, strict border controls, and early use of measures like social distancing and widespread testing. However, the proactive approach of Aboriginal-led organizations, with government collaboration, played a vital role in protecting remote communities. Now there are signs that these acts of self-determination could bring lasting change in the way health challenges are addressed.

Like many First Nations people worldwide, longstanding health and social inequities have left Australian Aboriginal people in remote communities with a high burden of disease. Compared with non-Aboriginal people, they are twice as likely to have coronary artery disease and 2.9 times as likely to have diabetes, according to the latest figures from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Aboriginal people also die on average around eight years earlier than the rest of the population. This gap in life expectancy has improved but not closed despite years of government reports and recommendations.

The relative vulnerability of First Nations people to COVID-19 also comes from the failure to invest in public housing that meets the needs of Aboriginal families. Several generations often live under one roof and are highly mobile within kinship regions. Housing was on King’s mind when placing travel restrictions on the lands of the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY Lands). “[T]he way that Anangu lived—closely together—if it got in, it would spread quickly and the morbidity rate would be high because of that,” he said.

With so many people in one dwelling, facilities like kitchens and plumbing are often overburdened. In 40 percent of very remote community houses these basic facilities don’t work, according to AIHW data. This was exacerbated when people returned to their traditional homelands for safety during the pandemic, on expert advice, leading to a spike in trachoma, a bacterial eye infection.

Although Aboriginal people in towns or cities also have difficulty accessing good housing and culturally-sensitive health care, remoteness creates an additional hurdle. Early in the pandemic, patients with respiratory symptoms had to be flown to Broome for coronavirus testing. They then stayed in isolation in hotels until their test results came back from Perth, according to Dr. Anderson. New facilities for rapid point-of-care COVID-19 PCR testing in community health centers have since erased some of the tyranny of distance.

Infographics by Kylia Ahuna

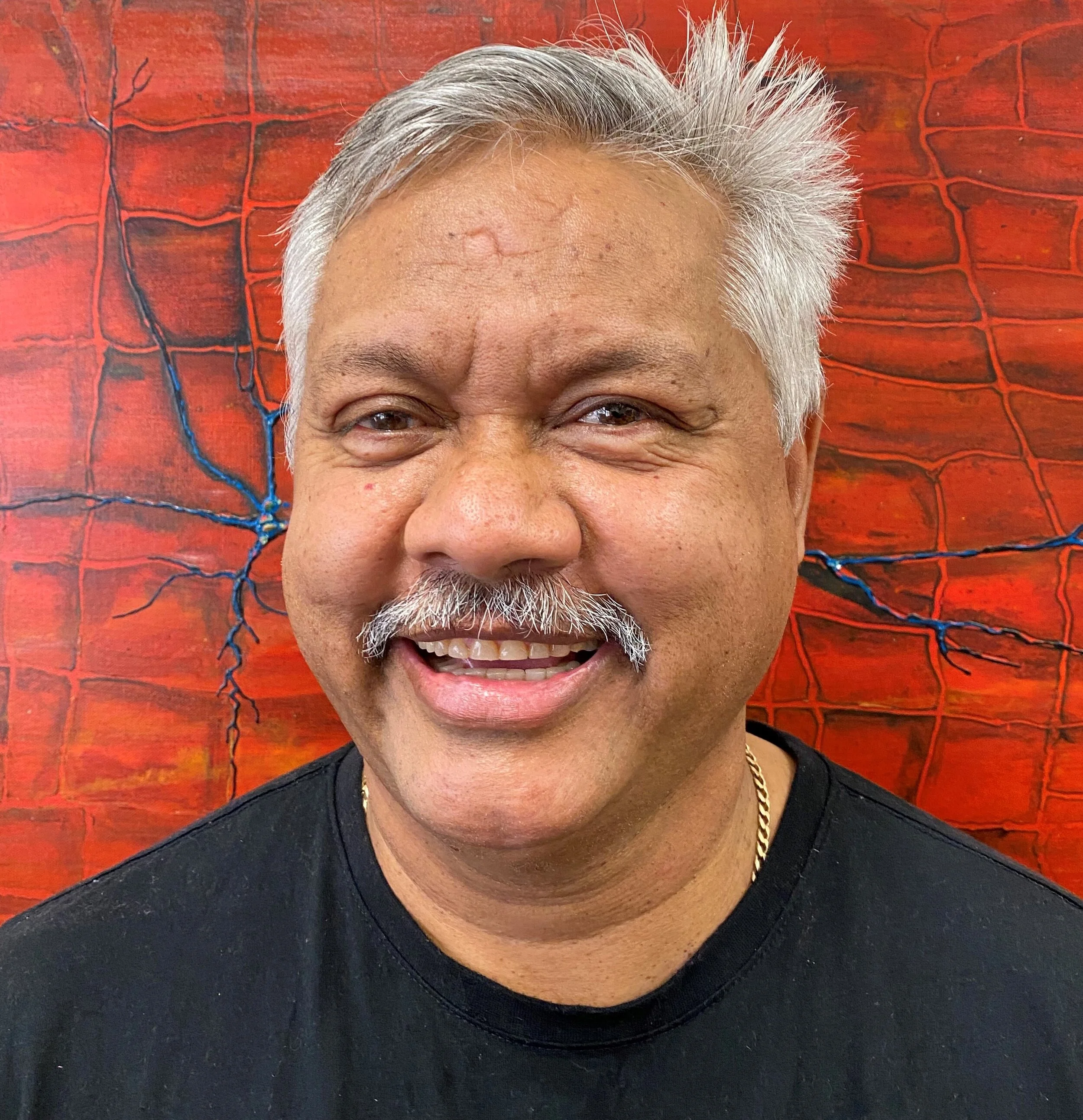

Richard King is the general manager of the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands. (Photo courtesy: APY Lands, Facebook)

KAMS runs five health centers in the Kimberley region, one with a doctor on-site and the rest staffed by remote area nurses and Aboriginal health workers. In the dry season, doctors visit from Broome or Perth to provide specialized services like psychiatry and ophthalmology. Before COVID, Dr. Anderson had her eyes on expanding telehealth services to allow year-round access to doctors for community members. In a meeting in January 2020, a colleague had told her it would take five years. “And two months later we were doing it,” she said. “Because we had to, because of COVID.”

The pandemic has amplified underlying disadvantage, but it has also shown community resilience, technological innovation, and positive adaptation. Early messaging on social media like Twitter and Facebook emphasized cultural imperatives such as protecting community and elders. Targeted government grants supported increased use of social media, and traditional outlets like radio, for public health messages. These were often delivered by respected community elders in the many Aboriginal languages spoken in remote communities.

For King, engagement with technology is one of the longer-term positive outcomes. “People are . . . tapping into trusted websites and health sites to gain accurate information, and I think that will continue,” he said.

Some health benefits arose during the lockdown, which officially ended in July 2020, although travel permits remain in place in many remote communities. King said that, following efforts to ensure additional deliveries, there was a significant increase in sales of fresh food in community stores on the APY lands. A better appreciation for the ways viruses are spread also led to more handwashing and people staying home when sick. Dr. Anderson also pointed to increased rates of flu vaccination in 2020, before COVID-19 vaccines had been developed, as evidence of this awareness.

New partnerships with government, such as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Group on COVID-19, have fostered a sense of optimism for some in the Aboriginal community-controlled health sector.

Historically, changes in remote health care policy have come from government departments not well connected to remote communities. “It was very rare for us to be consulted. We were always just told,” said Dr. Anderson, a member of the advisory group. Now, she said, there is a strong group of public health professionals who give a clear picture of remote Aboriginal health to a government who is listening.

However, in the same way that heat waves grab more attention than climate change, once the wave of the pandemic passes, poor housing and health care access will remain as obstacles to better health for First Nations people. Those are issues, Dr. Anderson stressed, we “can’t afford to take our eyes off.” Lasting impact may come from the experience of community-controlled health organizations being at the table with national leaders. “This has been powerful for the decision-makers, to be able to draw on our knowledge and powerful for us to be able to determine our own response to COVID.”

Postscript:

Since the time of writing, the Delta variant has come to some Aboriginal communities in western New South Wales (which were not in lockdown). Collaboration between community-controlled health organizations and government health authorities is still needed to protect vulnerable populations.

Staff are preparing vaccinations at Bidyadanga Health Centre, Kimberley Region. (Photo courtesy: KAMS)