A.I. Tool Narrows Pain Disparity for Black Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis, Study Finds

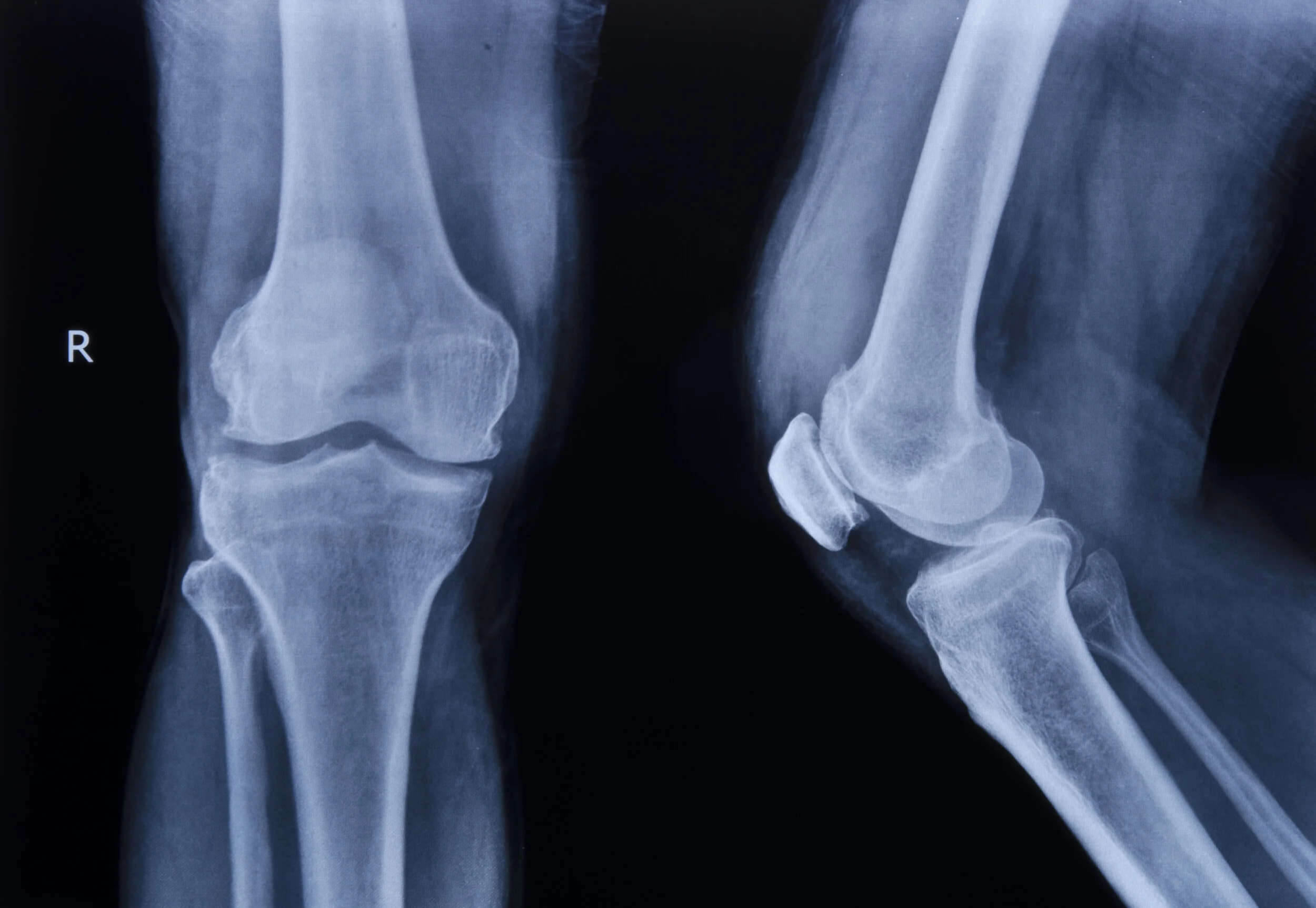

An X-ray of a patient's right knee seen from the front and side. (Photo courtesy: iStock)

Debra’s doctor thought she was too young to get her knees replaced. At 50, Debra had walked tenuously into her doctor’s office to see about treating the source of her daily knee pain. The doctor took X-rays and wrote a prescription. But Debra returned to her home in rural North Louisiana with only anti-inflammatory pills and more questions. The doctor said she would “be all right,” Debra later recalled, telling her, “Okay, here, take these pain pills and go home.”

For Black patients with osteoarthritis like Debra (a pseudonym to preserve her privacy), X-rays leave an incomplete picture of their experience. In the United States, many Black patients report feeling a much higher intensity of pain compared to white patients with similar X-rays, according to Dr. Staja Booker, a nurse scientist at the University of Florida’s College of Nursing who recounted Debra’s story. A study published in Nature Medicine earlier this year points to one explanation for this pain disparity: radiologists, grading the X-rays of both groups, have long used a standard metric called the Kellgren-Lawrence grade (KLG) to assess damage to joints. But derived from a pool of only white patients in the 1950s, this racially biased measure eclipses radiologists’ view of factors that may contribute to Black patients’ knee pain.

The research team led by Dr. Emma Pierson, a computer science professor at Cornell University who studies inequality and health care, has since devised a new measure for osteoarthritis patients, one which combines their X-rays with personal reports of their pain. The study is the latest in an arsenal of efforts to use artificial intelligence tools to tackle health disparities. Among them are other approaches to address health information needs based on search engine results and adjust for the historical underrepresentation of women and minorities in clinical trials.

Pierson and her colleagues trained a computing system to predict how much pain a patient is experiencing by looking at X-rays of Black and white patients’ knees in the Osteoarthritis Initiative’s publicly available database. This neural network, which can recognize and model patterns in vast amounts of visual data, “is doing something fundamentally different than what a human does,” said Elizabeth Krupinski, a professor of radiology at Emory University interested in medical image perception, who was not involved in the study.

The neural network inspected tens of thousands of X-rays, pixel by pixel, eventually correlating certain physical features of the knee with patients’ reported pain. The system then created a heat map of the affected areas in the knee that may be causing pain in Black patients. The network was able to reduce the disparity in pain between races by nearly half.

The key to this success was showing the network a diverse dataset of knee X-rays with the patients’ self-reported pain levels. That way, it could learn to interpret the images based on how patients judged their experiences, rather than how a radiologist would read an X-ray.

“X-rays, regardless of how we score them, are never going to map on perfectly with the pain experience,” pointed out Dr. Kelli Allen, a professor of rheumatology at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, who studies racial differences in osteoarthritis pain and was not involved in the study. “Self-reports of pain are always going to be the best way to measure pain.”

The researchers gave the neural network few instructions except to take note of any patterns between the X-rays and pain reports. “It's a way to try and remove any bias” from radiologists’ readings of images and their interpretations of the Kellgren-Lawrence Atlas, explained Dr. Amanda Nelson, director of the Phenotyping and Precision Medicine Resource Core at the Thurston Arthritis Research Center in North Carolina, who was not involved in the study. Using this approach, the study authors stepped outside of traditional X-ray scoring to create a new measure.

With osteoarthritis in the knee, there’s a breakdown in the cartilage where the thigh, shin, and kneecap bones meet. The rubbery tissue that usually shields the three bones and enables them to move smoothly becomes rough, frayed, or worn away until bone grinds against bone. This progressive damage to cartilage isn’t found in people aging without the disease, revealing that the changes aren’t just due to wear and tear. Osteoarthritis further results from the body’s unsuccessful efforts to repair and rebuild tissue, causing extra bone to form and an excess fluid build-up, inflaming the joint. “There’s a lot that we need to learn about this really very common disease,” Nelson said, including how the knee’s structure changes as osteoarthritis progresses, how to measure pain in new ways, and what drugs can fight the disease.

The study authors were not able to discern exactly what the neural network is seeing. But Nelson suspects the algorithm may be able to see something human radiologists miss, such as the spots where bone is beginning to harden just below the surface of the cartilage. It’s possible those areas may be causing more pain for Black patients. Krupinski notes that human radiologists’ perception can be limited when it comes to discriminating textures in an X-ray and identifying small objects. “The challenge now is to find ways to convey to radiologists why [the neural network] is rendering that decision,” Krupinski said.

This method accounted for some of the unexplained pain disparity, but other factors lie beyond what’s occurring at the joint as seen in X-rays. Addressing this pain disparity will require considerations that extend beyond the physical differences in Black and white patients’ osteoarthritis to broader psychological and social factors, such as Black patients’ higher rates of stress caused by systemic racism, which can contribute to pain overall. Consider also: Some patients report no pain even though their X-rays show an advanced progression of osteoarthritis. Meanwhile, others report excruciating pain but have X-rays with few hints of disease.

Many Black patients often have to convince health care providers that their pain is real and severe, added Booker. Understanding experiences of pain across races will be pivotal in ensuring that Black patients with X-rays of low severity are not overlooked when seeking care for osteoarthritis. “Patients want to be heard,” said Allen. “They want to talk about their pain experience.”